Closing Time: Premrock, Art Vs. Work, Hip Hop Influence, and the Tom Waits-To-Tending-Bar Pipeline

Every once in a while, while I'm tending bar, a customer will ask me, "what do you really want to do?" I usually, after clenching and unclenching my fists for a while, say, "this. I want to do this." When I say it, I'm telling a truth. Not that what I "really" want to do is have that conversation (I do not, at least not with them), but it is true that I do want to tend bar. Among other things. Other things that, while being done by me when I'm not at the bar, have been removed from being any of the customer's business by dint of them having an annoying face.

The rapper Premrock tends bar as well. I imagine that the emcee, born Mark Debuque in Allentown, Pa. to a Filipino father and a Slovakian mom (“both American through and through though”) who “were woefully miscast for each other but did their absolute best during the time they were together,” and I share certain ambitions, some realized and some not, and I also imagine we share (early morning coke dreams aside) reasonable expectations. If either of us ever seriously considered a level of fame that would allow either of us to be, fuck, marry, or kill Machine Gun Kelly, we’d both probably have chosen actual famous people as our chief influences.

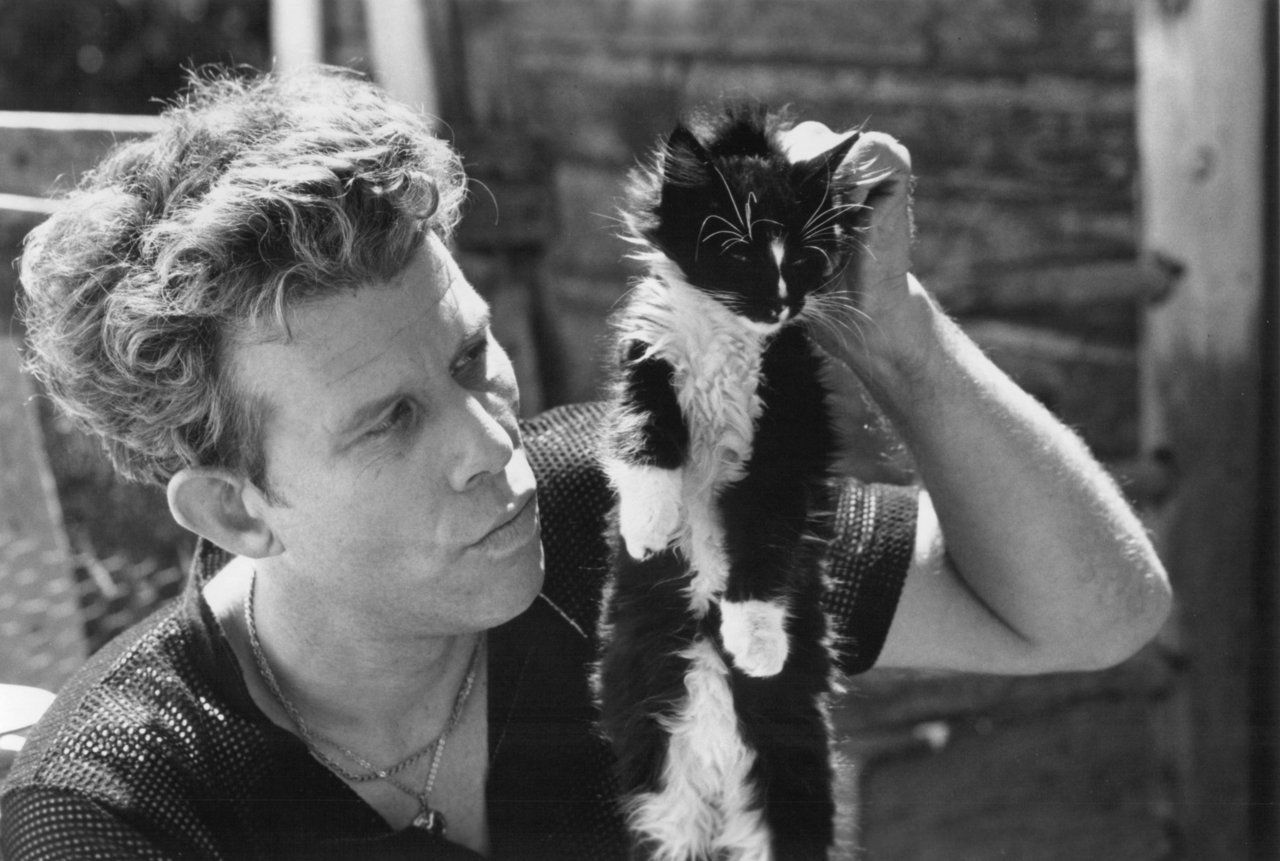

As a youth, I went with Nick Cave and Andrew Eldritch. Two fine artists, but hardly mentors for amassing great fame or riches. Premrock, whose purview is an unshowy but abundantly sly rapping style over meticulously curated soul beats, was a bit smarter in his choice of role models. But only just. Besides the the influence of “golden age” rappers, Def Jux abstractionists, Ghostface et al*, and the sardonic-eyed, caustic-commenting peers (such as billy woods** and Curly Castro***) he’s been milieu-ing amuck with for the last decade, the artistic influence Premrock cites most often is the genius/punchline (and vice-versa) avant-troubadour; Tom Waits. The emcee mentions Waits in every interview, references specific Waits lyrics on his most recent full length, Load Bearing Crow’s Feet, and, in 2012 devoted an entire 13-track tribute album to the Patron Ass-flask Saint of Hep Cat Loserdom. “The Waits references are obviously all over Mark's Wild Years as every song is a direct interpolation of one of his,” Premrok says. “Beyond that, he always sneaks into my subconscious. Songs like ‘Soft Machinery’ being a marriage of Burroughs and Waits come to mind.” And, to this day, Waits is “a tremendous influence.” If billy woods is famously disinclined to attend Nas at Carnegie Hall, Premrock is front row center to a flophouse with a string section.

*”Wu Tang is the greatest miracle of music in my opinion.”

**“woods is probably my fav rapper right now, and that’s sometimes weird to process, but I felt that way for a while. He’s just found his voice impeccably now and says all the shit the universe misses, in a succinct way. Heartbreaking and hilarious couplets. He’s on top of his craft.”

***”Castro is the most natural rapper I’ve ever met. He owns the badge of artistry like no one I know. He keeps me sharp and very hungry to produce great material… No idea how that many geniuses ended up as friends and collaborators but the world is better off for it!”

Now, to be sure, Tom Waits is very successful. He’s world renown, often mentioned in the same breath as Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen. He’s critically beloved and simultaneously, in the face of those who choose to focus solely on his oversized angle-headed hipster persona (or, more commonly, his funny hats), entirely critic-proof. His songs have been covered by Queens of The Stone Age, Sarah McLachlan, Meatloaf, The Ramones, Patty Smyth, and he probably earned enough from the Rod Stewart cover of “Downtown Train” to purchase, if he’s feeling particularly puckish, his own competing Scottish football club. He’s played the most defining part in a number of archetype setting movies and, in a few kinda boring movies, he’s consistently been the least dull aspect. Before opioids and marijuana use supplanted alcohol as the leading shorthands for class-neutral existentialism, he was the leading cause of problem drinking amongst a certain kind of young men (18-25) who (maybe) didn’t technically suffer from the disease of alcoholism, but not for lack of trying. He’s duetted with Bette Midler. Back when the Divine Miss M was her own cool kind of kitten. But, even as Midler long ago abandoned her mermaid-wheelchair audacity in favor of Streisand-adjacent #resistance sass, Waits could probably duet with her again, on a special episode of The View to be broadcast live from the 9th Circle of some Clinton Library hell, and still maybe pull it off.

All that being said, Tom Waits is famous and successful in the way that Sun Ra, Jagermeister, and Wolverine are all famous and successful. Iconic (in the correct usage of the term), but not terribly handy as an aspirational template. Not sure how a baby Premrock thought making a mood board of Tom Waits’ dissipated wordplay was going to shake out. But if the concrete-crooning singer of “Jockey Full of Bourbon” is one’s artistic North Star, it doesn’t take a monkey’s paw to point out the inevitability of working at least a couple bar shifts a week.

“Never thought I’d be a bartender, I don’t think. Never thought I’d be extroverted enough, but it was born out of necessity when I came to New York in 2008. Climbed the ladder of the service industry to get to the booze quite frankly. I’ve been bartending in West Harlem 149th and Broadway to be precise for damn near eight years. Before that, it was rich people downtown and I hated that. Now I know exactly what to expect and they treat me quite well. A marriage of both convenience and mutual respect. Hard to find here or anywhere really.”

So, Premrock is a bartender. Which, without romanticising the gig, can occasionally resemble a Tom Waits song. Not as much as those inclined to cosplay disolution might like to think, but enough so to the point of there being a good reason why, if you play something on the jukebox off of swordfishtrombones, most bartenders will press the "skip" button hidden behind the bar. But, artwise, the theoretical Tom Waits monkey’s paw only comes into negative play if one is dumb enough to come at the songs of Tom Waits (or, while we’re here, any art) straight. Which Premrock ain’t, and therefore doesn't.

“Waits has influenced my continued attempt at fleshing out the perfect gambler with a heart of gold,” Premrock says, “the charming, sympathetic yet frustrating documentarian of the unseen. In line for the free clinic but also volunteering at the soup kitchen. He/she/they have a lot to offer but a lot of spinning plates to drop too. Invest at your own peril. They find the shine in the doom. It’s a talent and a curse. This character can navigate any situation but often finds themselves in a bind they can’t undo. Toothpaste which can’t be put back in the tube. I think I love this type of character because I do love bars. I love vulnerability. I crave realness and despise facades.”

“Waits definitely writes about class. Love and war have to consider class. I think he examines it through the lense of various character traits. Christmas Card from a Hooker in Minneapolis is an example. He cares about the downtrodden. The truck drivers making ends meet. The nighthawks at the diner nursing a cup of joe because anywhere beats home. He’s a friend to the lower class I believe.”

(To be clear, Premrock wasn’t volunteering a theory of Tom Waits’ class consciousness out of nowhere… I asked.)

Some degree of permission to sketch the characters found in Premrock’s raps might have been granted, in part (and along with a number of depressive straight-up literary types like Sylvia Plath), by Waits. Or, rather, Tom Waits’ stories serve as a variation of the character sketches that Premrock heard in the rap he also grew up with. (The issue of artists like Waits being historically granted permission to sing about crime, without pressure from fans to have firsthand knowledge of said crime and without the burden of the Carceral State possibly using said crime songs against them, in a way that *cough* other artists are not pressured or burdened, is a separate essay unto itself.) But if Waits’ art has served as a gateway, Premrock, be it in his solo work, his collaborations with Fresh Kils, or as part of his long running collaboration with Curly Castro known as Shrapknel, is savvy enough to enter the boho spirit of the work; world-weary anti-heroes looking through the hi-ball glass weirdly, while avoiding the lure of anachronism. Protagonists may lounge around in sleeveless t-shirts, being well versed in Beatnik Culture 101, but they’re no more invested in Even Cowgirls Get The Blues than they are in the minutia of professional tennis. They're not pale imitations of Tom Waits characters. They’re proper losers who enjoy the music of Tom Waits, as well as the music of Cannibal Ox. In this way, Premrock keeps his proceedings studiously uncorny.

The trap of writing imitations of Waits is treacherous. And not just in the characters. The danger of writing songs that are less songs about hanging out in bars, and more songs about songs about hanging out in bars is ever present. With either no relevant life experience to draw from, or lacking the talent to speak that lived experience in one’s own words, countless songwriters have taken the work of Waits (or Lucinda Williams, The Pogues, The Replacements, Kris Kristofferson, etc.) and simply re-transcribed that work. A bit faster perhaps, maybe looser as a point of pride, occasionally with the reason for the narrator’s fatalism changing from “having to work in the coal mines” to the more relatable “having to tour,” but the end result is the same. A genre-spanning school of blech; lousy with faux-sympathetic, actually-cruel Piano Man balladeers and cruelly sentimental beard-rockers; types who presumably hear Nebraska as an audio pamphlet, commissioned to be written by a young Bruce Springsteen by the Omaha Chamber of Commerce, in order to encourage looky-lou tourism to all the drug store parking lots and company-store dive bars that the Great Plains had to offer.

Luckily, instead of rewriting witness statements of dissolution, Premrock talks about his job. He talks about growing older. He keeps the stakes ostensibly low, even if that means, on the surface, tamping down the drama. His shaky souls’ narratives may not rise to the arson of Frank’s wild years, let alone the mini-melodrama that surrounded poor Small Change’s grubby fate. But lower stakes isn’t the same as no stakes. Premrock’s characters are graying before they’re dying, but the dying is still there. If casting off for Singapore will have to wait till the G line extends past the Polaski, the world–be it through Big Pharma or various diasporas looking to get over–still has a way of showing up at one’s doorstep. The emcee himself isn’t “walking Spanish down the hall.” Rather, our dude’s existential grime is rendered as “this next left up ahead, that’s me.”

“I worked at a record store in high school and ironically we didn’t buy vinyl, but a couple came in shortly after I purchased my first sampler and drum machine, asking if they could simply donate a whole lot. The owner said he wasn’t interested but ‘talk to the stoner in the back’ (me). After much procrastination, I finally called the number they gave me and caught them on their last night in town. ‘Come get this vinyl tonight, and you’re gonna need a truck.’ My girlfriend had a truck as fate would have it, and liked to help me out (before the cascade of disappointment truly fell) and agreed to help me out. I left their house with a definitive cornucopia of classic albums. Jazz, Rock, Funk you name it. My education took on higher learning that night, and Tom Waits was among the stacks. Waits, to me, is the best of us. As humans. A gutsy and honest song writer, and I immediately was drawn to him.”

I recently finished the Marc Ribot collection of essays, Unstrung. Years before he played guitar (with additional playing from Keith Richards and Robert Quine) on Tom Waits’ Rain Dogs, the album that would establish him as a wildly inventive, silvery and sharp player, Ribot was a hipster with a job. From 1974-1978, before he made (and, in part, made) the New York no-jazz downtown scene, the guitarist toured Maine in a no-rent, quasi R&B outfit. Technically speaking, this was a “gig” as opposed to a “job.” Living the dream even before the dream took off. In the pages of Unstrung, the way that Ribot describes the stresses of playing bluesy scales to indifferent audiences, in and around prosaic equivalents of Salem’s Lot (where the mills/factories rising from the dead to feed off the living would be quite reasonably seen as welcome lateral move from how they operated previously), sure feels like work. Grueling work at that.

Premrock belongs to a clique of Marc Ribots; brilliant artists eminently familiar with the grind. I’ve seen billy woods and Elucid perform at Central Park SummerStage to a rapturous crowd. I’d also seen them perform to sparse audiences at grimy rock clubs where the rappers on stage were inarguably working way harder than the passively unaggressive bar staff. It’s only been recently (extremely recently) that maverick soul composers like Willie Green, Steel Tipped Dove, or Messiah Musik have gotten even a tenth of their due. Curly Castro recently had a medical issue that made clear that, whatever he’s doing when not making masterpieces like Little Robert Hutton, it doesn’t come with health insurance. Zilla Rocca is asking for $1,000 for a digital download of Vegas Vic. Considering the labor and care he put into the album, and considering all the lesser artists getting rich on NFTs or from throwing cake into crowds in between spinning thirty second snippets of rancid pop choruses, I figure Rocca rates it.

I don’t know if my firm belief that artists (and writer/critics) should work jobs (preferably unrelated to their art/writing/criticism) is born of genuinely felt aesthetic ideology, or from my needing to work one of those jobs because I don’t make enough money from art (or writing or criticism). Or if my lack of massive financial success in those latter arenas is born, in part, from some unacknowledged unwillingness to sacrifice the safety net of a job and, you know, really go for it. But, until a larger chicken-to-egg-to-chicken chronology is revealed to me, I’m going to stick with the notion that being forced to interact, on a regular basis, with people other than artists and writers and critics, does make for better art. Or work, I guess. Which art, you know, is. And if that’s vaguely condescending towards non-artists, that’s ok too, as any condescension in that regard is a two-way street. A little tension between occupations is healthy. That’s why it’s so funny when firefighters and cops get into physical brawls with each other every other time a Happy Hour on Staten Island draws to a close.

(I realize the above is somewhat contradicted by Marc Ribot’s essays–dude never held a straight job in his life–and possibly by whatever the rest of Backwoodz roster was doing to keep the lights on before that masses–as it were–and The Alchemist got onboard, but I’m thinking about work–in whatever form–and how it informs art. I’m not prosecuting a law case. Don’t bother defunding me; I already blew the tank money on Bandcamp Fridays.)

I’m not going to press the comparisons between Premrock and Tom Waits. It’s an interesting influence. One that is uncommon. Gary Suarez told me that Blu references Waits in a song and G-Eazy sampled him, but he couldn’t think of anyone else. I’ll put Aesop Rock down as a fan, but Blockhead is largely indifferent, and list kind of peters out…

“woods may not have listened to Waits super intently, but I know he has heard records of his. There's a lot of parallels between them as artists as well. I know Zilla Rocca is a Waits fan. I've spoken with a lot of others over the years, but I'm really failing to remember who right now. Waits casts a wide net of influence and I know his son, Casey, is a big hip-hop fan. There's been some bleedover in that regard. You can also hear Waits embracing more hip-hop sensibilities later in his career.”

The influence is not uncommon in a way that’s particularly counterintuitive. In the same way that few rappers outside of Juelz Santana (feat. Yelawolf) (and, uh, I guess Elucid and Premrock on occasion) are drawing from Dylan just because Zimmerman has a bar or three; there’s enough rhymes floating around, even pre-hip hop, that nobody has to look to white folks in eccentric hats for inspiration unless they really want to.

And it’s not like, outside the specific tribute of Mark’s Wild Years, Premrock has affected any of Waits’ vocal tics. Even then, Premrock’s flow never veers into gravel-throated. Possibly out of respect for the earth-dies-screaming oeuvre of Mystikal, but more likely out of respect for the fact that Premrock’s natural register is compelling enough; the cool, swaggering, walking bass line underneath “Romeo Is Bleeding,” rather than the Howlin’ Beefheart wail that defined Waits’ approach to the human voice from that point onward. As I said earlier; there is a clear lyrical influence, but just as many points of departure. So, in the absence of either vocal affection or lyrical pastiche, when I consider Waits’ influence on Premrock, I consider it as an influence of ethos; a way into the rapper’s work, not the point itself.

“Everyone is 89% more revealing after the third drink.”

There’s a million ways to tell a truth. At least, off the top of my head, there’s five I can think of. There’s the sideways archetype-ography of storytellers like Waits. There’s grandiose statement profundity; good for writers of religious tracts and the more stadium-minded indie rock acts. There’s the raking through the prosaic (such as on the, if not directly influenced by Tom Waits than at least influenced by the experience of dating Tom Waits fans, last Fiona Apple album) until pain reveals itself as truth. There’s the brutalist, oblivion-ha-ha fatalism exemplified by the original Def Jux philosophers and Premrock’s Wrecking Crew comrades in Cargo Cult. And there’s the combination of the four; where the day-to-day is so lousy with truth, where death by violence is a possibility but death by death is a certainty, that it’s no wonder that the only reasonable way to deal with all that truth is through day drinking. Premrock excels at this last fumbling towards revelation. Resignation is his wingman and co-pilot. He’s called “last call” enough times that it’s become a mantra.

This should not be confused with giving up. “Taking the edge off” with a drink can be a cope, or a personal disaster (one that’s all too often extended to one’s family and loved ones), but it can also, for a lucky few, be a way through.

“Waits made his best music once he got sober. I don’t necessarily know what that means for me but I respect it and think it’s an important fact. He was a caricature at first. A bar fly poet with a gravelly touch. That couldn’t last. No character can remain static and he illustrates that. He’s gonna die old as hell and on his own terms. That’s a great outcome. I want my second act to be like his.”

I don’t know for sure if the emcee Premrock will ever get rap rich enough to quit tending bar. He’s catchy and charismatic, and God knows–and has shown (with the careers of Ka, Jean Grae, and Premrock’s chief patron, billy woods as evidence)- that, even if popular hip hop ostensibly shares popular culture’s obsession with youth, a degree of success is still possible–through grind, luck, talent, and grace–after thirty. While Premrock’s sanity is probably net-neutral, careerwise, his body of art/work commands its own inherent respect.

And even if the Good Ship HipHopPop has sailed… so what? Sometimes “doing the work” entails pulling a double, with no overtime. And tending bar is dignified and cool as hell. I don’t know the rap industry, but I do know that the port of call for hip hop Fame & Fortune operates from the same tributary as that of indie rock fame and fortune, post-hardcore fame and fortune, and spoken-word poetry fame and fortune. And, in those regards, I live on the docks, under a tarp. Without wishing any financial hardship upon Premrock, I’d be delighted to have such wry, charming company with which to watch both our deserving pals and mediocre betters board a Big Black Mariah and sail off to wherever it is that pop culture winners, and all the other squares freed from the tyranny of trying, sail off to. Hell or Coachella, presumably. And, when Premrock does get his deserved wealth and success, either through merit or falling into a relationship with one of Kanye’s exes, I’ll be happy for him. Delighted in fact. The tattoo teardrop I’ll get for every year he’s away will be a cute reference, not a sign of grief.

Worst case scenario, I hope that at least one of us ages into being able to pull off wearing an eccentric hat.

Thanks for reading! Please share and subscribe. Otherwise those jerks at Substack win.