On Being A Real Nuanced Cat: Rhys Langston Complexes the Veil

Since the turnover of American leadership from the performative, unsuper villain malice of the Trump administration to the ostensibly well intentioned, differently incompetent, porcine lipsticked empire maintenance of the Biden White House, I have a little joke that I like to make that isn’t all that funny. I like to say, “nuance is back, baby!” It’s an injoke for fellow nerds who have made the same questionable choices in taste that have resulted in a shared understanding of Death In June memes. In the straight world, the word “nuance” is a positive; a term to describe the inherent complexities of nearly any situation. In the countercultures I exist in, however, “nuance” has long been shorthand for the fencewalker rationalizations of artists and art that oftentimes skewed more fascist than complicated; noise acts that “hate everyone equally” but sure seemed to have plenty of white friends. Black metal folk artists decrying religion in general, but, funnily enough, Islam in particular. Fans of Death In June calling the act “provocateurs” while DiJ leader, Douglas Pearce, put out double album benefit CDs to raise money for the HOS Miliz. Other classic examples include the trope of loving the first “non racist” Skrewdriver album. Or covering Burzum (or, say, existing as what was essentially a Peste Noir tribute act but with better drum sound) and claiming to “separate the art from the artist,” until Trump made even that rationale untenable, and then just pretending that all your previous gestures towards Galtian spiritualism were a lark, a misunderstanding, the youthful dalliances of any mid-twenties child blissing out on Varg Varkness’s riffs for the first(ish) time. You know… nuance! I found, and find, the mangling of the term darkly amusing. Admittedly, mileage may vary.

Like repeating a piece of bro-ish slang ironically as a teen until it became wicked habitual, I have been jokingly saying “nuance is back, baby” for so long that I woke up on one washed and dreary morning to realize that I may, in fact, believe that nuance is indeed back. Whether it’s subtweeting my way through the recent noise scene kerfuffle, seriously considering watching some questionable acts at Psycho Fest next year, or indulging the passing thought that maybe Portland, Oregon should be walled off entirely and designated an Insurrectionist National Park (with a series of elevated monorails constructed so that tourists and podcasters alike can traverse the town borders in safety, gawking at tagged and population controlled Proud Boys battling it out with black bloc ninjas on the streets below), I have felt the siren call of bleak, both-sides-suck cynicism knocking at the walls to my heart. Seeing friends and peers, many of whom speak of both Spotify and Israel with a vehement heat strong enough to power a DIY block party, spare nary a public fucking thought for civilians suffering in Afghansitan, hasn’t particularly tempered that onset of cynicism.

But, of course, cynicism, cheap and largely inaccurate, is what it is. And it’s to be avoided. My reasonable self might bristle at the constructed lie of Biden’s New Normalcy. My worst self might writhe around at all perceived hypocrisies. My most petty instincts might tell me that everyone is a phony and that, really, the best place to exist is above it all, as though such a thing were possible. But I take a breath, do some reading if I’m tempted to forget actual history, and remind myself that both sides do not, in fact, suck equally. The Democrats might be corny, but keeping Planned Parenthood funded is not. Liberals might have a gratingly situational affection for the FBI, and they may have inflicted the Ted Lasso Christmas episode upon the world, but liberals also gave us the harmonies of CSN&Y, which in turn led to the harmonies of Alice In Chains. Plus, liberals gave us all those other Ted Lasso episodes and they believe in the existence of COVID, both of which are solid as hell. And, even if the alt-city of Portland has irked since the day I realized that heroin was never going to be my hard drug of choice, the fact remains that antifa, regardless of the occasional fuckhead, are brave and provide a genuine public service. And god knows that, unlike the fucking Proud Boys and their inability to pull off the near-impossible-to-fuck-up Fred Perry gentleman thug look, antifa knows how to layer. I still think the national park might be a good idea, but only so there can be a monorail with the Dead Moon logo emblazoned on every car.

But, yeah, what wear are we talking about? Oh right… nuance. As much as I appreciated the “in these dark days” publicist emails of the last four years (and genuinely have always appreciated the artists who exist in opposition to Empire regardless the administration), I think maybe we were all a tad hasty in ceeding such a fine and useful word like “nuance” to sunwheel tattooed free speech advocates and amateur WW2 historians. While I’m not eager for a return of paste-pot scalliwags romanticism genocide under a tuneless veil of eco-pessimism and Evola quotes, I also can’t say I’m ready to embrace a future where all art is judged by the number of relationship red flags its protagonists raise among the very smart-but-dumbest of society. Maybe, rather than either (easily avoidable imo) extreme option, maybe it’s time to dip our collective toes into the Wendy-and-Lisa-warm waters of edgy but thoughtful, borderline-tasteless-but-still-deeply-considered, almost-but-not-quite-offensive nuance.

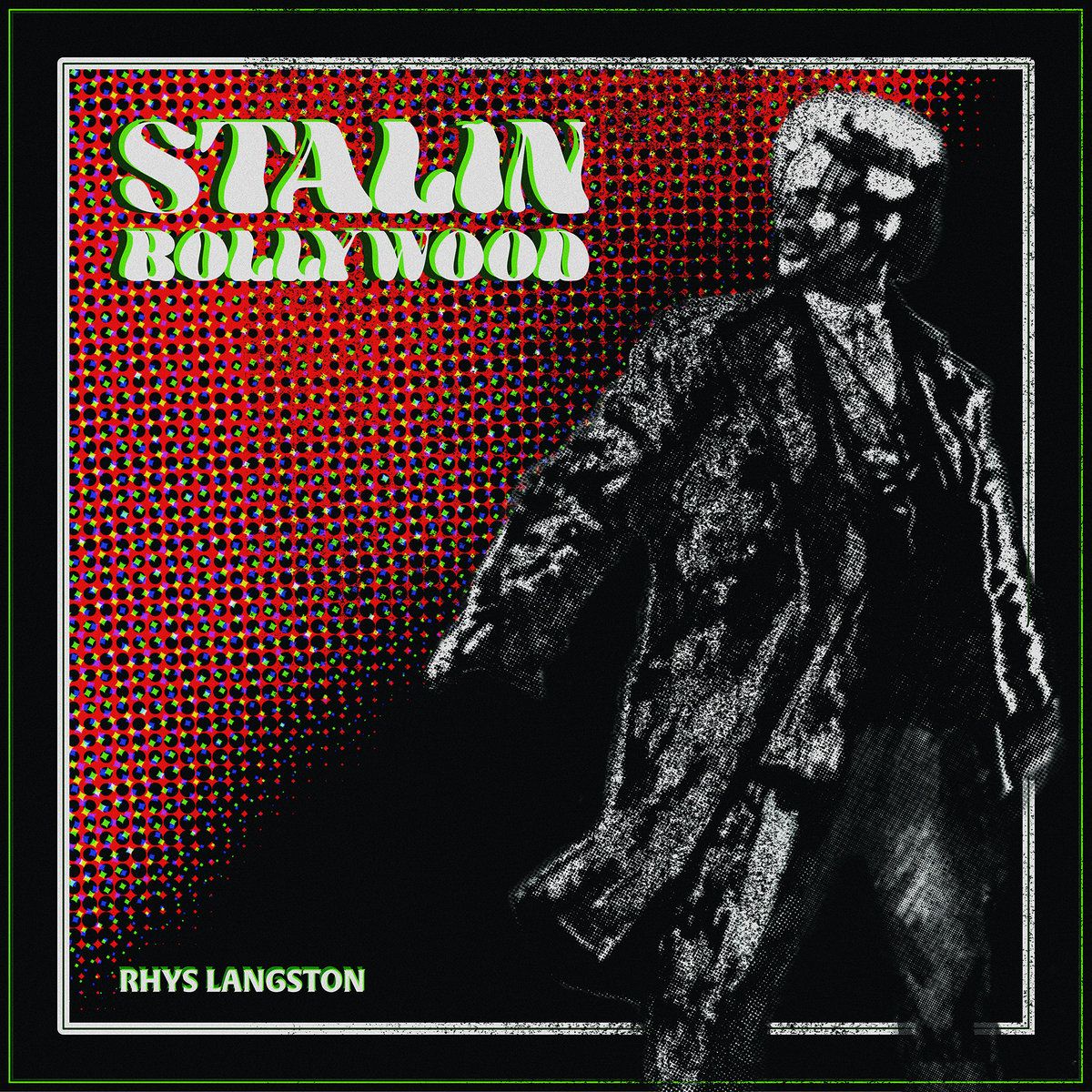

Allow me to introduce you to the Los Angeles rapper/new waver/provocateur, Rhys Langston, and his newest collection of swinging, peppy, punkbeat provocations; Stalin Bollywood. The tunes on the album are TV on the Radio as performed by the Thrasher Magazine house band, the lyrics punch any which way plus loose, the vibe is Decline of Western Civilization 101, and, if Langston was as popular as he deserves to be, he’d be completely fucked. Basically, “Si culture de l'effacement n'existait pas, Rhys Langston faudrait l'inventer.” But also the record is good as hell.

Stalin Bollywood, like all of the Rhys Langston catalog, is also -as much as any street trash stick n poking or hair metaler giving drunken interviews from the pool- a part of the proud Southern California musical tradition of wiseass negation, baked noir dry under a dying sun. Wearing the same They LIve, illusion stripping, sunglasses of Busdriver and T.S.O.L., and inhabiting the same end-times funhouse as Pharcyde and the Dangerhouse punks, Langston knows and distrusts a good time when he sees it. He wages the same war all artists from the region, with the exception of maybe The Eagles, waged; to not disappear entirely under the force of all that infernal fun.

“A lot of people say they're from LA and it's, like, The Valley, or it's the South Bay. And I don't like to shit on people like that,” Langston says, “but... I'm from LA proper. Let's say that.” The rapper/poet/visual artist/Los Angeles Unified School District substitute teacher grew up with his older brother (Kirk Podell, currently of Children With Dog Feet and Subversive Rite, and ex drummer for Neo Cons, Neighborhood Brats, and MORE!) and their parents, first in Los Feliz “while it was still affordable,” then moving around Los Angeles and spending some time in Hollywood (“the armpit of the city… a terrible place”). When the parents’ marriage ended, Langston split his time between neighborhoods he calls “emblematic” of his parents’ individual background. His Jewish father lived in the “very Hasidic” neighborhood of Beverlywood, while Langston says his mom (the actress Marie-Alise Recasner) “was in View Park, which is very close to Leimert Park, which was an area that's historically black, one of the few to not yet be gentrified (maybe not ‘gentrified’ so much, because there's money there, so the gentrification is a different animal or whatever), but an area yet to be broken up as a black neighborhood.”

His parents are both in the arts (“Our parents were actors,” he says, “are working actors. They’re not people who, you know, had super big breaks or whatever. But they paid the bills acting.”) and they encouraged the same in their children. While Langston’s brother taught himself to play the drums in order to pursue a career in street punk, Langston dabbled, with an interest in music that waxed (exploring joke rap in 6th grade) and waned (“The elementary school we went to was one of the few in the city that had an orchestra program. So I tried to learn music formally that way… I was like, ‘no, not gonna happen.’”).

When Marie-Alise Recasner remarried, it was to a film composer who further encouraged Langston to pick up an instrument. “And I plucked out a few things,” Langston says, “and I was like, ‘ah, I don't really get it.’ You know, ‘I like music... I don't really get it.’ And then in my teen years I was just like, ‘oh, I kind of want to do this.’”

Leimert Park is the neighborhood where both Project Blowed, the Los Angeles underground hip hop touchstone (which Langston sums up as “LA’s version of Nuyorican Cafe, but, like, Nuyorican was maybe more with, like, slam poetry and Project Blowed was more, like, you'll get your head taken off freestyling…”), and the equally influential World Stage jazz scene originated. Growing up in the area, Langston was only dimly aware of its history, distracted as he was by the other two touchstones for artistic evolution: making music from a place of teenage indecision, and “hanging out.” In college, Langston knew what he didn’t want to do; be boxed in or trite or, as he puts it: “I was just like, man, I'm not going to do some shit over YouTube beats or rips of DJ Premiere or Ninth Wonder beats.”

But what he did want to do was less clear.

“I started to produce stuff and spent a lot of time in my dorm room being like…” Langston attempts to explain, “...maybe I was alienated. Maybe I was trying to be alienated.”

While continuing his more formal training in visual arts, the drive to be rapper came in 2012, from that divine fountain of beauteous plenty that gives sustenance to all artists, more sustenance than even teen ennui or urban jazz programs can hope to provide...

“I think it was, like, the ego thing,” he says. “I heard a lot of what people were doing, and I was like, ‘I can do this better than this person.’ So I really, like, actually tried…”

“And was pretty, pretty bad for a while,” Langston says, “But,” he adds, undercutting, like all true artistes, the respect owed to human ego with some healthy self loathing (and simultaneously saying something I found to be genuinely profound), “I think maybe having better tastes than ability at the start was helpful.”

The question as to whether rap is poetry is a treacherous one. On one hand, the comparison is vaguely patronising when applied to any non-explicitly poetic-on-the-page form like, say, rock or folk lyrics (in that the implication is that any of these musical genres need to be justified by comparisons to a form that isn’t inherently superior, just older and more respected by some theoretical higher echelon of culture… not that, in practice, culture particularly gives a shit about poetry…), but the need to valorize by comparison takes an extra sheen of condescension when applied to a medium like rap (“rap is the poetry of the streets” etc), where the comparison sometimes hints at the belief that rap has to be poetry because otherwise there’d be no black and/or poor poets. On the other hand, set to the page and out of the context of beats, plenty of lyrics from any of these genres can work just fine as conventional poetry. And plenty of rappers consider themselves poets. So why be too uptight about it. For someone like Rhys Langston, who collects his lyrics into books of poetry, the question is not moot, exactly, but given the further complexity it deserves.

“My project, Language Arts Unit,” Langston says, talking about his 2020, well regarded full length, “came out with a book where I basically, without being like Lin-Manuel Miranda, you know, I was trying to exalt rap a little bit and be like, ‘well, you know, rap is this in-between child. It is this ideological force that is also a response to ideology. You can kind of portray the use of language as part of a lineage of literature, or in response to the exclusivity of the canon and all that. How I approached it, in the book, I presented the lyrics as poems, and I wrote them and copy edited them. I was like, this shit is enjambed this way for a particular reason. You won’t maybe hear it that way, but if you read it on the page, you might be like, ‘Oh yeah, that makes sense.’ You know, I was my intent and a few people backed me up. I can't say, you know, Kevin Young or anything is going to publish me in the New Yorker, but certainly a few people got that impression. And, yeah, I'm of the belief that it's like a Yes and No thing, where, you know, I think it really is what you make it. I think if someone's trying to disrespect rap, I'll be like, ‘yeah, it's poetic.’ But if someone's trying to be too jaunty and overcompensating about it, I'll be like, ‘just... it’s dope.’”

Langston talks about everything with the same level of complexifying, two (or three or four or five) contradictory theories given the equal weight that they, as viable truths, warrant. It’s this omnivorous quality that led him, through a friendship with fellow leftfield thinker SB the Moor, to the equally omnivorous record label Deathbomb Arc (the California avant-everything label that put out Langston’s collaboration with beak>/Portishead’s Matt Loveridge). This connection in turn led to Langston’s relationship with Jeff Weiss, the journalist and publisher of theLAnd Magazine, whose site, The Passion of Weiss, has long been essential reading for anyone who cares about hip hop (or California culture in general).

“Brian (of Deathbomb Arc) sent this album that I dropped in 2017, Aggressively Ethnically Ambiguous, out to a few people. Jeff got a link to it. Then I saw him in person and I was carrying around CDs of it in my car. And it was actually a design, like a lyric booklet, and I put a little bit of money into a digipak… and I gave it to him and he was like, ‘oh, this is cool.’”

Weiss has since become Langston’s biggest online booster (“He's definitely been the earliest person who went to bat for me, to the degree he has, and has really been the only person to go to bat, to that level.”), and has further backed up his praise of the rapper by adding Langston to the roster of POW Recordings, the small hip hop label (with a considerable lineup of talent- including Fatboi Sharif and Gabe Nandez- that belies its size) that is an outgrowth of Weiss’s blog/enthusiasm.

Langston credits his Leifert Park background for giving him the path/community that eventually brought him to his current label’s attention (see: The Virtues of Hanging Out), as well as his own worldview, where he consistently undercuts his own warranted self-regard with a healthy portion of potential self-sabotage (which, in this case, worked out well). “As much as I came to music being like, ‘I can do that better,’' he says, “I've always also balanced it out with, ‘I'm not that important. There’s other people doing it.’ So I approached (Weiss) like, ‘Hey, you like my stuff? Oh, well, I happen to have something for you. Here you go.’”

If previous Rhys Langston recordings like Language Arts Unit and last summer’s EP, Grant Money Raps, fit snugly within his label’s general vibe of “Smart, But Not Irritatingly So” rap, it still speaks well of both Jeff Weiss’s commitment that POW agreed to put out Stalin Bollywood with nary a bat of the eye. Or it gives evidence for the label owner’s commitment to a larger heritage of Los Angeles sound as, on the face of it, Rhy’s Langston’s newest album, while still being very much a hip hop record, is as much the provocatively wisenheimer rat-a-tat-tat of Angry Samoans (or at very least the vaguely malicious surf-funk of Long Beach’s Suburban Lawns) as it is Ras Kass. Langston himself cites the classic Dangerhouse and Burning Ambitions punk compilations as direct influences on the songs, along with Devo, T.S.O.L.’s Beneath The Shadows, and the combination of sequencing and live instrumentation used on the Thomas Dolby albums his mom used to play all the time. But if such esoteric influences bothered POW Recordings at any point, they don’t appear to bother the label now. In the album bio, the label flatly rejects the notion of Stalin Bollywood as even “a stylistic curveball,” saying that, “this project, in fact, is a logical progression.”

The label bio ain’t wrong, exactly. While the majority of Rhys Langston’s work sonically draws from R&B, jazz, and all the other genres or micro-genres or flute-heavy vibes utilized by the beat makers Langston favors, all the other black derived sounds (i.e. all of them) were lurking under the surface. His work for Deathbomb flirted with noise/industrial rap, his self-produced beat on his Full Frontal Incumbent mix tape was practically choral drone, and he never seemed married to one particular sound above others. Vocally, even in the previous density of language of Langston’s older work, he always conveyed layers of literary allusion and analysis (directed both inward and out) in such a nimble way that you’d have to check the lyric sheet to find out that you didn’t know what half the words meant. Even at his most abstract, he was never anti-pop. Delivered in a boom bap, Bugs Bunny lilt, lines like “Raps in fugues, sestinas/Prussian Blue iambs begrudges/Antifa farmers market luncheon/Yeah, hair parted like a truncheon” all sounded as needlingly fun/funnily needling as any new wave or post punk jam. At the end of the day, hip hop, new wave, or popular punk are all genres where the traits, be they aural or ideological, of a wascally wabbit are easily carried over from one mode to the next. So, if the basement show snare clatter that opens the album, the Black Flag bassline of track two, the fake english accent of “Dirty White Boys,” or the TV on the Radio cover, strikes the listener as jarring or needlessly novel, then the listener hasn’t been paying attention. (Or the listener is just deeply weird… who doesn’t like TVOTR?)

Where the listener of Stalin Bollywood might be forgiven for doing a double take is in the album’s themes, lyrics, and song titles. The first song on the record is titled “hos on my dick ‘cuz I look like a drawing of the Prophet Muhammad.” Track two is “the pope is a(n) (unrepentant) rapist.” Even before reading the lyrics or watching the video for “hos on my dick…,” the shadow of trite edgelord-ism, if not necessarily actual -phobia, looms. Even I, an aging hipster well over-versed in irony, who owns a Watain belt buckle, romanticises skinhead culture to a truly idiotic degree, and is on friendly terms with multiple ex members of Swans not named Thor, saw the song titles and uttered an involuntary and audible “woof.” Partially because I feared an artist/person I genuinely like being cast out of polite alt-society and partially because I don’t actually like jokes about The Prophet or care for the word “rape” used as mere metaphor. Like many people, what I do or don’t find offensive is highly situational (though, in my defense, it is not, unlike some motherfuckers in this biz called show, transactional). Being familiar with Rhys Langston’s art and ethos, my assumption was largely one of good faith on his part. And a cursory listen rewarded that assumption; adolosecently edgy chorus statements complicated and recomplicated by every word before and after (though "Dirty White Boys" does appear to just be about terrible roomates). But I’m not every listener/reader. In this regard, Rhys Langston fully understands any discomfort and/or irritation, to the point of wondering why more people aren’t mad at him. In fact, in talking to him, it becomes clear that no one is less at complete peace with the intended provocations of Stalin Bollywood than Langston himself.

The liner notes for Stalin Bollywood says, in part, “Beyond black and white divides along ideology or linear understandings of modernity, the semi-nonsense name, is to say we are trapped in well-produced, convincing, and gaslighting spectacles of brutality and subjugation, not wholly consenting to the history we uphold or futurism on which we are set. And what’s more, the very means of critique we have are compromised. If in our frustration, flagrancy is the only resort, are we truly prepared for catching the crossfire?” In other interviews, the rapper has called what he attempted to do an attempt to “appropriate shock value,” almost to talk about talking about what can’t be talked about, without actually committing the theoretical ill-intentioned offense. I can admire the tightrope Langston is attempting to walk. On one side is base outrageous expression, on the other is the comedian’s sometimes workable, but often flimsy, “it wasn’t a racist joke, it was a joke about racism” rationale. Both sides are pretty much lava, and there’s Rhys Langston up on that tight rope, spinning his umbrella and trying to talk about talking about outrageous notions, with hopefully enough electricity to jolt but not so much that anyone gets hurt.

Langston’s mother once told him to not write or say anything that he couldn’t defend, so there’s a painful quality to listening to him pretzel through an intentionally contradictory piece of art that he clearly felt like the moment demanded. “There's a question of accountability and the conversation that happens after something. Then again, I guess it also depends on the collateral damage of that shock value, right? If like I talk about the prophet Mohammed and I'm not even doing the blasphemous thing, I'm suggesting the blasphemous thing and suggesting a suggestion of it in a world that's Islamophobic, am I, am I still contributing to the problem? Even when I try and poke at the idea of sensitivity, you know?”

While getting into Langston’s intent, it’s worth touching back on one of the album’s sonic elements; the synth sounds lasering and burbling throughout, the “new wave” sounds. Rap, since its inception, has been building on the electro sounds (from Kraftwerk to Egyptian Lover) that new wave, at its most sleek, itself drew from. And, while Langston’s cited influences of Thomas Dolby and Devo are not typical reference points, rappers sounding like Berlin (band or city) is hardly novel. But, typically, (and to be clear: conceding the point that many distinctions between the technological vamping of The Cars and Zapp are either arbitrary or racial) rappers who are best known for “new wave” inspired beats, such as Kanye or Cudi, utilize that ‘80s coldness to indicate either depression or a malaise inspired by the vacuous result of their life choices and the vacuous nature of of those around them (and the resultant dystopian intercourse with those people… and the emptiness they feel afterwards… or during…). If not malaise, the sound is used as party rock; electroclash mosh pit fodder, as exemplified by Ninjasonik and any number of other tight pants rappers of the first decade or so of the 21st Century. Rhys Langston arguably has a kinship with all those names, but on Stalin Bollywood, his version of new wave alternately hews to the spastic Devo interpretations of contemporary synth punks and the aughts new wave of TVOTR, using both interpretations of an ‘80s sound in the way American Psycho used ‘80s AOR. As a signifier (and jaunty backbeat) to scathing absurdity.

Despite the veer of irony, Langston’s actual politics, sometimes even expressed in only half-jokily earnest (“Don’t want a birthright as colonizer/Unoccupied as sympathizer/I remove my two eyes/And set ‘em in a two state solution”), are pretty clear. There’s nothing actually offensive going on here. Just the occasional hint that something offensive might happen. Thematically, if not sonically, what he's doing isn't too far afield from the (also criminally overlooked) rappers, Cargo Cults, and their Nihilist Millenial project. So it may have been overly cautious on my part, and a bit of wishful-of-self-destruction on Langston’s part, to think that there'd be any attempted cancellations.

Langston admits, “I think what allows me to do this and go full force is that I am, I do in my heart of hearts, believe that people have more capacity than either they know or that they've been led on to believe.” But he also says, a tad wistfully, “I don't know, maybe in a contradiction, I was too subtle in my flagrancy. Not that anything was unsuccessful, but maybe what could be read into the album is that in some ways I might be too subtle in my flagrancy. I know that would probably make something less aesthetically enjoyable if, like, you can hear me winking at the camera.”

Sometimes, sadly, an artist must settle for just making something aesthetically enjoyable. Can't purposefully lose 'em all!

All this might (on my part) be… a lot, considering we’re talking about an eight song EP by a rapper who is not quite famous, and who partially concocted his skate-punk tantrum because he was tired of being pigeonholed as a conscious or “academic” rapper. But I’ve made worse art for worse reasons. And Rhys Langston is a grappler with Big Ideas in a world that rewards settling for received wisdom, and then repeating that received wisdom via lyrics, criticism, and social media. Sure, there’s no shortage of Free Speech Provocateurs. But those guys and gals largely fucking suck and are just repeating Barry Goldwater talking points for fun and (enormous) profit. Maybe it’s just because I grew up reading Lisa Crystal Carver, but I don’t know that it’s an ideal situation where only Nazis and Substack dorks are encouraged to be provocative. Not to mention that Rhys Langston raps way, way better than Bari Weiss writes. (And, even here, he’s prone to a self awareness that none of these chumps could dream of, saying at one point in our conversation, “I've asked myself why my vocabulary is so flush in terms of shit I hate.” A question that many of us could maybe consider asking ourselves.)

When I told Langston about my private “nuance is back, baby!” joke, he wrote, “We are in a place where so much repeated flagrancy and lack of decorum over the last few years has us wanting some form of normalcy, but that in itself is inherently rickety and an imagined genteel fantasy. Where outrage, shock value, and insensitivity might have been overwrought before, one could say now we need a few (tasteful) jolts to combat a campaign-- a placation industrial complex if you will -- that wants to convince us everything can be alright the way it was.” Which I thought was great.

He immediatly followed up with five texts second guessing himself.

Thanks for reading!