Never Get Old

WARNING: This is one of those “making an artist about oneself” essays that you may hate. And you’re not wrong to hate the form. Half the time, I do too. But this is my newsletter and it’s what I feel like writing. So, if you don’t want to read an essay about Sinéad O’Connor that’s mainly about me—with little analysis of O’Connor’s actual music—I don’t blame you. Close that tab and be free. But if you, a certified weirdo, have some sort of freakish interest in Zack As a Young Sinéad O’Connor Fan, please keep reading. I’m happy to have you here.

Shuhada' Sadaqat, 1966-2023

While I am not—and never once have been—a punk rocker, I do subscribe to some of the basic tenets associated (in theory, if not always in practice) with the lifestyle/genre. By disposition, if not ideology. Meaning, I don’t know that I ever needed to be told that someone wasn’t any better than me just because they were on stage, and I was on the floor like some kind of sea anemone. Meaning, I have loved rock stars, I have envied rock stars, and I have wanted to be them. But I have never really thought of a rock star as something to be a “fan” of, with all the supplication, dreamcasting, and confusing five-level stacked-interchanging of parasocial responsibilities that fandom entails. Even with Kurt Cobain, when I was a teenager playing Nevermind on my walkman so much it caused the guidance counselor to contact my mom (and this was before Columbine!) I wasn’t really a “fan.” Cobain didn’t seem that different from the older skaters in town. And, annoying as I was, those dudes came around to me in time. I figured, fuck it, Kurt and I would probably run into each other eventually.

But before grunge, I was a fan of one rock star, once.

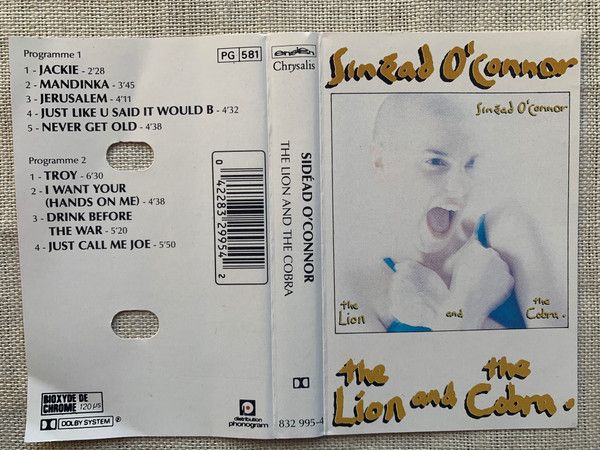

The Lion and the Cobra came out on November 4, 1987. I was twelve. I assume I bought it at some point during the next two summers, when I was thirteen or fourteen, when I would be under the thrall of older YMCA camp counselors from New York City. I’m not really sure of the details; whether it was from older kids or just pictures in Rolling Stone Magazine that I first heard about Sinéad O’Connor. In my memory, De La Soul’s 3 Feet High and Rising was the YMCA summer camp album before The Lion and the Cobra, which isn’t chronologically possible.

And while I’m sure that I “hadn’t heard anything like” Sinéad O’Connor, I’m not sure how meaningful that insight is. I was a kid. I hadn’t heard anything like most things. All the deads—Grateful, Kennedy, Milkmen—were equally new to me. Between 1987 and 1990, I had my lil’ mind blown by some new Public Enemy, Godflesh, or Throwing Muses every other month. Even if I hadn’t paid the slightest due attention to my mom’s Buffy Sainte-Marie albums (or my sister’s well worn copy of Joshua Tree), it would not have been novelty which drew me to The Lion and the Cobra.

Knowing that I was all-in from the onset, and acknowledging the fact that I simply didn’t have enough context to “appreciate” just how fine O’Connor’s voice was, how strange and bracing her songwriting was, I’m hard pressed to explain why I was such a fan. But I was that; with every song on The Lion and the Cobra being a vessel for fantasy and endless pacing the span of my bedroom. I don’t have enough paying subscribers to warrant too embarrassing a detailing of these fantasies. It would be a cute detail if I could remember any specific individual(s) who might have starred in these mini-dramas. But the truth is that my adolescent desire was genre fiction by necessity. At that age, an interdimensional secret agent succubus—seeing me at the Berkshire Mall, having some sort of mole-hair fetish, and begging me to come back to her space lair to read poetry aloud from my tear stained journal—seemed more of a viable fantasy than wasting my imagination hit points on, like, any of the girls who trounced me in the 8th grade student council elections. The Lion and the Cobra’s singer herself didn’t factor into my adolescent musings. The characters I heard and communicated with in O’Connor’s songs were more ghosts, sailors, some amorphous kind of Irish person indistinguishable from aliens and superheroines, and the various manifestations of my own incredible need to be interesting. Preferably interesting in a way that involved a lot of suffering on my part. I took to The Lion and the Cobra the way that others take to power metal or Conan the Barbarian; a high drama album of adventures where I was the hero of a mixture of Dragon Magazine, Heathers, The Highlander, Camus’ The Stranger, and a smattering of Penthouse Letters (for when I ran out of cool things I’d say or do that might inspire a song as wild and knowing as “Just Like You Said It Would Be”).

With O’Connor’s art so beyond rational judgment/appreciation, with that goddamn proxy-of-divinity voice, like angels too confident for competition, and without any aesthetic of my own beyond the sheer mileage of my inner life that the album ran through, I was a fan. I guess. I didn’t actually, at that time, care about Sinéad O’Connor as an artist or human. But, again, I was a teenage boy. I didn’t really care about anyone as a human. I like to think the music helped remedy some of that solipsism—it certainly has maintained its spiritually riotous power—but who knows?

But I do know that, by 1990, I was as much a Sinéad O’Connor old-head as anyone in the chlorine-misty YMCA-pool semi-wilds of North County Western Massachusetts. So, when the singer came to town, supporting her newly huge I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, I immediately got tickets (even if her becoming mega famous, on the strength of “Nothing Compares 2 U,” didn’t exactly jibe with either the insularity of my fantasy life or my developing sense of not being super into People Enjoying Things).

O’Connor played at Saratoga Performing Arts Center. I don’t remember everyone I went with. I think the driver may have been an older guy who may (or may not) have done some real uncool stuff to me when we were both much younger, but I suppose his having a car outweighed whatever (maybe) deep seated trauma I might have needed to suppress in order to hear “Troy” live. (To be clear, if I can even trust my childhood memory in the first place, suppressing it was worth it!)

While disclosing embarrassing details, I should also mention that, at fifteen, I was in Drama Club and was briefly into wearing blouse-y white button downs and embroidered vests. Even though I would very soon transition fully into Sessions Catalog Minor Threat t-shirt wearing, baggy shorts-ed adolescent fury, I was at that stage more likely to reference Morrissey referencing Oscar Wilde and try to pass off thoughts cribbed from The New Yorker review of the Twin Peaks pilot as my own. I was a swashbuckling/swooning aesthete in training and, Sweetness, I dressed the part. And it was draped in this temporary persona—white pirate blouse untucked over blue jeans so distressed they verged on despairing—in which I attended my first Sinéad O’Connor concert.

The show at Saratoga Springs was a week after O’Connor had ruffled some bald eagle feathers by refusing to play the Garden State Arts Center until the venue dispensed with its traditional pre-show rendition of the “Star-Spangled Banner.” So there were about ten or fifteen men protesting the concert. I don’t recall where I stood vis-a-vis America in general at the time, but I knew where I stood regarding the singer of “I Am Stretched On Your Grave.” Admittedly, as one might feel about America (or at least about its ostensible ideals), I preferred the older stuff. As I was about to dress like a Beastie Boy and only listen to Fugazi for a couple years, I wished I Do Now Want What I Haven’t Got had as much howling as the debut I incongruously related to so deeply. But, just like the protestors who loved America despite their service in Vietnam being a bit of a let-down, I wasn’t going to let a few diminished returns make me into a stinking traitor. So I squared up to one or two damaged souls, still wearing their trauma literally as badges on their camouflage vests, and defended the honor of my favorite singer. To my credit, I wasn’t as obnoxious as I could have been. I luckily channeled my dad and talked at a normal volume about free speech, reciting all the liberal (and correct!) cliches about dissent being patriotic etc. If I was excruciating, the protesters indulged me. Or they were too nuts to discern condescension. Who knows. But I remember it as stressful but civil. I imagine I thanked them for their service (veterans of foreign wars love rote gratitude from teenagers dressed like extras in a Jellyfish video) and I’m sure at least a couple men told me I’d know better when I was older (haha).

What I learned later was that Sinéad herself was in disguise in the midst of the protests, wearing a wig and sunglasses and watching the kerfuffle unfold. When I found this out, the dramatic potentials within my inner life fucking exploded. Alas, if Sinéad O’Connor ever sent me a long, perfumed and handwritten letter—calling me courageous, erudite, and shockingly handsome in my defense of her honor—it must have been intercepted by my new enemies in the American Legion.

The show itself was great. I mean, of course it was. One of the greatest singers of the last fifty years, at a height of her powers that I’m not sure ever descended? It was, in my recollection, perfect. (If I’d wished she’d played more songs off of The Lion and the Cobra, I kept it to and from myself.)

Afterwards, I waited outside, behind the Arts Center, where the tour bus was. As I recall it, there weren’t many of us. But I know some of the others had roses. I wasn’t that kind of fan. So, when a small lovely Sinéad O’Connor walked past me I handed her my vest. She took it graciously, thanked me, and kept moving. I can’t tell you if I remember what she actually looked like in that moment, or if I remember some photograph I saw in a magazine, placing that image in the necessary slot in my mind so as to maintain the sweetness of the memory.

Later works, being more specific in their politics and the personal, didn’t allow so much for fantasy. Or my own developing sense of empathy prohibited it. Fandom is essentially a solipsistic pursuit, if a self-negating one. So I stopped being a fan. And didn’t bother looking for a replacement. Who could possibly take her place?

As the years went on—and I only listened to screamers and thugs, and I very much didn’t purchase O’Connor’s album of standards—I still scanned whatever press I saw of her, looking to see if she might be wearing a black and gold, intricately threaded vest, about six sizes too big.

That first album never left my speakers for long. Even as some of the emotions it evokes have changed. For whatever it may be worth, “Troy” remains the only song (besides “Wichita Lineman”) that makes me cry no matter what mood I’m in.

Now Shuhuda’ Sadaqat is dead, at 56. Given what's known, perhaps by her own choice. Which is a grievous thing, but I can’t question the decisions of anyone, let alone an artist who could only live as she could. The world remains for us to do the same, as best we can, with the diminished voice that comes—directly or indirectly—with this absence.

The testimonials have poured in. Tori Amos, the President of Ireland, Duff McKagen, the dude from Gladiator… Bad as Twitter is, it was far better in mourning than Bluesky, where 90% of the memorials were devoted to O’Connor’s tearing up of the Pope’s photo on SNL in 1992, with a smattering of “Black Boys on Mopeds” or “she boycotted Israel!” This is not to critique artists (like Ted Leo, who I love both personally and aesthetically… and didn’t do what I’m talking about anyway) who have been fighting the real enemy all their lives, and also understand what a song might be for. But it quickly became clear that huge swathes of people who largely share my politics have become incapable of processing grief or art, or any moment that can’t serve as some cudgel against the fascists that seem to always be baying at their online door. I suppose I’m doing the same thing here, looking for enemies amongst almost-friends, when I should be mourning like a normal person. Still, as the lady herself said, her activism didn’t fuck with her money. It fucked with the money of men who had never known her worth, or the worth of anything outside of money, in the first place.

At dinner, on the day O’Connor’s death was announced, Zohra’s dad asked his family if they knew about the singer who’d died. So we played songs from her albums and live performances at the table, each of us pulling up favorites on our phones, concurrently discussing the reverberations of trauma and the similarities between Irish melodies and those from the Middle East and South Asia. Zohra’s mom and dad listened to each song (her mom taking noticeable pleasure in songs performed since Sadaqat/O’Connor’s conversion), and they both agreed that it was all very sad, that the songs were beautiful, that the singer was as well, and that she—like nearly everyone—deserved to be loved better than she was.

Thanks for reading.