Eight Unfinished Essays on Marquee Moon

You said, “Blah, blah, blah.”

-Tom Verlaine (1949-2023)

(Painting of Marquee Moon Album Cover by Nate Turbow)

Commemorating the dead shouldn’t be a competition. Like art, it is. There may be an infinite amount of beauty in the world, but beauty is like gold; it’s got the same arbitrarily set value and, if it’s going to be mined anyway, you and yours should stake your claim. Lest you wake up one day in some dusty horseshit town that you’d previously called your home, that’s just been renamed after some slick mouthed dude who, every time you see him at the saloon, pretends to be meeting you for the first time.

The digression is the point. As is obfuscation. To look at some things too square in the face is terrible. Our heroes are even older than we are, if you can imagine such a thing, and most of them smoked filterless cigarettes for longer than they didn’t, and loved hard drugs so much that the nine or ten holes they were born with were insufficient to the task of insertion. So, point being; best pull up the online thesaurus now. It’s not like the demand for eulogies is going down.

Disappointingly, googling variations of “Television,” “Tom Verlaine,” or “Richard Lloyd,” in combination with “Malcolm Young,” or “AC/DC,” doesn’t result in the counterintuitive gold one would hope. Closest connection I could find was Chuck Eddy listing both AC/DC and Television on his 150 Best of Albums of 1977 list, with Let There Be Rock as #19 and Marquee Moon coming in at #49 (one better than Christ Child and one lesser than City Boy). Sometimes the intuitive is unanimous, and there’s not much you can do about it. That said, in the same year that AC/DC played CBGBs as a lark, Tom Veraine argued strongly for the existence of a Venus de Milo with arms (“I fell right into the arms of Venus De Milo” etc.). A year later, AC/DC put out Powerage; the album with the only song (“What’s Next to The Moon”) in AC/DC’s entire catalog–with the possible additions of “Riff Raff” and 1990’s “Thunderstruck”--that even allowed for the possibility that Malcolm Young had ever heard a single note of a single Television song.

In 1979, on Highway to Hell’s “Touch Too Much,” Bon Scott would sing “She had the face of an angel/ Smiling with sin/A body of Venus with arms/Dealing with danger/Stroking my skin/Let the thunder and lightning start,” in effect arguing that a Venus de Milo having limbs was more novel than Tom Veraine had implied. And, while not explicitly denying the possibility of lightning striking itself, it seems like–if that was an imagery that AC/DC’s singer could imagine happening–he’d have used it. It’s not like the possibilities for double entendre inherent to literally anything striking itself would have escaped his notice.

A year later, Bon Scott was dead. AC/DC’s next album was Back In Black i.e. the Darkness Doubled. Karma? Probably not. Coincidence? Definitely. But what are the odds against any of us having been born in the first place?

It’s an indication of a life well lived when people use your death as an excuse to settle old scores. An absence must carry some kind of weight if–before the body is cooled, let alone buried–those in mourning take comfort as best they can; by taking shots at any motherfucker who dared to love the departed incorrectly.

It’s up for debate whether this is a standard that exists. Or if it’s a standard one we’d want it added to the (already too long and lax) grocery list of qualities applied to rate the relative importance of the dead, as if the dead might come back long enough to thank us. As if, by the time that happens, we won’t be on our own way to the grave, with some new bandwagon jumpers in the wings to claim ownership of our lives, deaths, and all the shiny detritus that comes with. If we even manage to survive our own grief or greatness long enough to both attract our own sad and smooth mourners, and make sure those mourners are still sympathetic to our cause. After all, there’s a trick to dodging enough existential stray bullets to make a story, without raising certain questions as to how honest we’re being when we claim that we don’t enjoy the sensation of being shot at. A little nuance is nice, but not so much that it makes the first paragraph of your obituary.

Setting aside the discussion of a loony-tunesian impulse for self immolation, let’s all agree that people die, the dead suck at debating, and it’s therefore left to the still living to decide which of the dead’s grudges get buried and which grudges are carried on, even if that means that something might be lost (or added) in the translation.

I think it’s very telling that the entire music world is mourning the passing of Tom Verlaine except for @thestrokes - one would think that they owe every fucking thing short of whatever their rich parents gave them to television. @brooklynvegan am I wrong?

— anton newcombe (@antonnewcombe) January 29, 2023

In that vein; if the members of a rock band that peaked in popularity twenty years ago and sounded a bit like Lou Reed and a bit like Tom Petty, who got their start in the golden age of bands being compared to bands that existed ten years prior, are deemed insufficiently distraught over the recent passing of Tom Verlaine, then maybe it’s up to a serially ornery singer–of a band that’s most famous for Not Being the Dandy Warhols in the documentary Dig!--to carry out what was (maybe!) Tom Verlaine’s last wish. Assuming that wish was that someone tell the Strokes, via the medium of twitter dot com, that all the Strokes riffs are Television riffs, that all the Strokes’ parents are rich people, and that the Strokes are not, according to Courtney Taylor-Taylor’s arch nemesis, sad enough online.

Additionally, there was this line from Dean Wareham’s appreciation of Tom Verlaine:

“His friend Patti Smith said somewhere that Verlaine ‘plays lead guitar with angular inverted passion like a thousand bluebirds screaming’ — but that says more about her than it does about him.”

Friction!

It’s hard to figure that Mr. Wareham didn’t know what he was doing when he typed that out. It’s a bit gauche to use the death of one of Smith’s (admittedly pretty numerous) dear friends to slide in a jab about how the poet might have–just once–allowed the ineffable to maybe overshadow the prosaic realities of just what screaming, bluebirds, or an electric guitar might sound like. Coming from me–a guy who has to stop himself at least ten times a day from comparing any generic hardcore band dujour to a tweety bird with angular inverted passions–Wareham’s critique would be pure hypocrisy. But, with a catalog that includes gorgeously melodramatic songs about standing in line to buy twinkies, the Luna/Galaxie 500 frontman has always been a vocal proponent of the earthbound. And Patti Smith seems to believe that aesthetics matter, so perhaps she would appreciate Wareham’s willingness to get a bit of dirt under his fingernails in defense of not relying on, you know, larger truths to accurately describe the external world.

There is a downside to being so earthbound, before death necessitates it. There’s a fine line between avoiding melodramatic gestures and just being afraid of looking like an asshole. Patti Smith has been a grandiose spirit since before she decided that what “Hey Joe” and “Gloria” really needed was a bit of spoken word. She was right about the latter. And she’s been batting better than a respectable .500 ever since. As for Newcombe, his potpourri of Hate Street jingle-jangle and hippified aggression isn’t for everyone, but you can’t claim that he lacks the vital artistic quality of being willing to appear foolish. Smith and Newcombe exist as outsized beings. And, while Smith is obviously the more talented of the two (I don’t think Newcombe would disagree or take offense at that), both of them inspire outsized passions in their fans as well, and it’s not passions predicated on the reasonableness of the artists in question.

Wareham, on the other hand, is rarely unreasonable. A lovely artist--the one I prefer out of the three--but eminently sane. Luna fans are pretty reasonable as well. Which is admirable. I like to think I’m reasonable too. I do hope that we’re not merely tasteful. I’d hate to die and have no maniac feel like I was ever wrong or wronged enough to warrant crashing my funeral and making a scene. The silence spreading is almost too much as it is. I’d hate to imagine it absent any men digging holes.

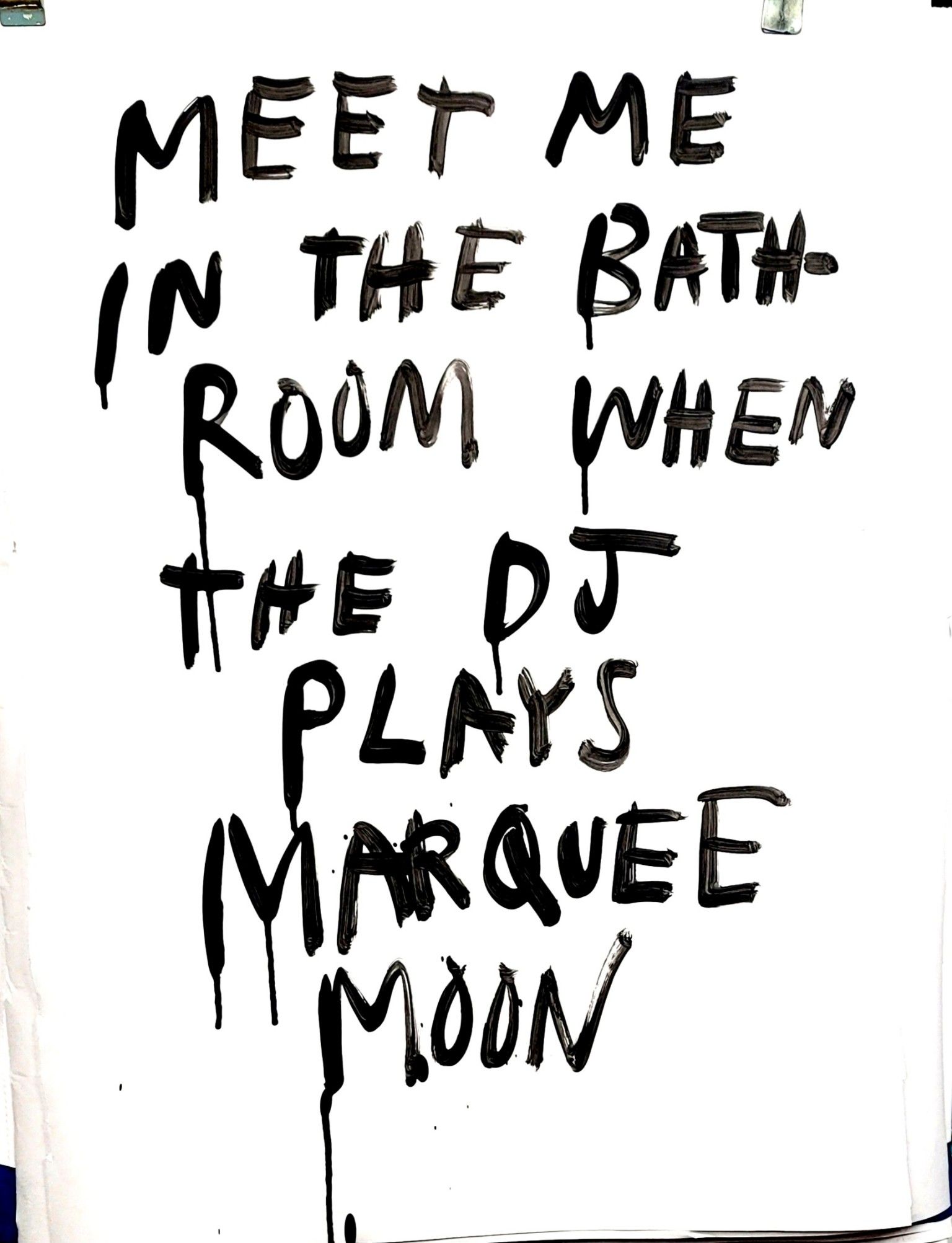

I was a bartender/barback in the East Village/Lower East Side as the 20th Century became the 21st. Meaning, I worked in East Village/LES bars when there were still jukeboxes and/or CD changers as the main source of music. Meaning, on any given night, even before a DJ might show up to play the exact same LES rock ‘n’ roll fare that was on the jukeboxes (but in a different order and with crossfades connecting the Saints to the Scientists), I listened to multiple songs off Marquee Moon at least twice a shift. Meaning, I have listened to Marquee Moon more often, with only Stooges’ Raw Power coming close, than any other album.

While, because there is only so much street walkin’ cheetah that even the most streets respecting ailurophile can be expected to take, tracks by the Stooges would occasionally get skipped (via a button hidden behind the bar so the bartender could pretend it was a juke malfunction). But not so for songs off Marquee Moon. In fact, I can’t think of a single LES bartender who wouldn’t, when there were no customers and the staff had already subjected each other to their respective CDR demos, put on Television’s first album, and play it all the way through. Even the old school monsters who only listened to the Bomp! Records catalog and/or Radio Birdman exclusively. Even the jaded-at-30-somethings who had been dropped by a major label before it was hip, who had been dressing in black denim and distressed VU shirts–wearing their hair longish and limp like depressive Tom Pettys–back when the only “American Girl” the Strokes were lifting from was their nanny’s favorite historically accurate doll collection. Even the bartenders who’d given up entirely; playing Some Girls on repeat– hardly hearing it as music–as they sullenly punched loose change off the bar. Even these soul survivors–who preferred the Heartbreakers to the Dolls and whose taste for experimental music extended as far as Dee Dee Ramone’s rap album but no further… even these bartenders would put on Marquee Moon. And they’d know every song, back to front, almost as well as they knew the exact date and time that New York City, as a cool place, had officially died (one week, to the hour, before you moved here).

Bartenders would play Marquee Moon, in a bar packed with cokeheads who had been punching in jukebox numbers all night, and who had heard the refrain of “I saw lightning strike itself” a bazillion times before. Bartenders would interrupt all that sweaty designing of playlists, even the curation of regulars who had put in a whole $5 in the jukebox and had been waiting nearly an hour to hear their ten favorite Mazzy Star songs. Bartenders would take a Saturday night rush, the lifeblood of their rent paying and cocaine purchasing power, and throw into that mix a slab of yowling poetry, jauntily threatening bass, and two Caduceus-tic guitars that seemed to be feeling their way through a migraine aura.

And playing the song in its entirety, all ten minutes and thirty eight seconds of it, would be the least passive aggressive thing a bartender would do their entire shift.

A bar’s “vibe” is important, and that vibe is communicated by more than the dismal state of the restrooms, the edison lights, or the implied racism of the “no caps, no sneakers” door policy. Obviously the clientele matters, but that’s arguably the rare egg that for sure comes after the chicken. And obviously the music matters. But it’s a rare album that is sufficiently a vibe unto itself to carry as much weight as a bar’s zany decor or the relative shirtlessness of its bartenders. To qualify, an album must be more than ambient and less than dominant, with a command that is subtle enough to be a prickling under the skin rather than something to sing along to or retreat from. It’s rare for an album to be background but somehow not; iconic but still indefinite enough that the bar vibe communicates a welcoming coolness rather than an intimidating cool. Rarest of all is the album that both staff and deejays can agree on, that’s music is–without being mandated by management–carried over from night to night, bartender to bartender, shift to shift. Without attempting to come up with a definitive list, what immediately comes to mind is; first and third Portishead, first B-52s album, Hot Buttered Soul, Urban Hymns, and Ziggy Stardust. If you’re tempted to throw in Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), you either hate your bouncers or never had to try to break up a bunch of adult skateboarders throwing fistcuffs as “Bring Da Ruckus” played in the background.

There are obviously others, but none come as quickly to mind as Marquee Moon. The closest comparison, in terms of being unobtrusively singular, is probably Sade’s Diamond Life. I won’t pretend that the music of Sade was regularly played in the bars that I worked in. But I suspect that in even cooler joints–whose diversity of staff background perhaps extended a bit farther than from Iowa to East 14th Street–Diamond Life fulfilled a similar function, in setting a tone of possibility (with just a touch of melancholy tension), as Tom Verlaine’s goosebump smooth operation.

Regardless of any previous uptightness regarding comparisons between Tom Verlaine’s guitar playing and bluebirds, flight metaphors are a given. Even when the snare is chittering underneath, and Verlain and Lloyd’s guitars alternate between subway slither and chatter, it all eventually takes flight, following the flight plan set by the bassline’s navigational chemtrails. Even if “pigeons wearing tap shoes” is off the table, and drone comparisons would be anachronistic by a half century, there’s something up in the air; a bird, a plane, something rising.

(As Television has been compared to the Grateful Dead in the past, I was tempted to draw some strained metaphor between “Elevation,” the Grateful Dead’s best known album, and the floating white plastic bag from the movie American Beauty. But every time I started typing the metaphor out, I began to gag. So let’s settle for “something rising” and keep it moving with our dignity somewhat intact.)

The style of playing–influenced by Jimi Hendrix but somehow distanced, through avant tendencies and a rough interpretation of psychedelics, from the Blues– exemplified by Verlaine (and contemporaries like Richard Lloyd, Robert Quine, Ivan Julian, not to mention key influencers like Richard Thompson) often gets compared to silver or quicksilver (derived from the olde english for “living silver”). The reason for this is probably because the playing is fluid, flashing, and brings to mind switchblades (especially to writers for whom swordplay tends to exist only in the romanticized theoretical). And for whatever other reason some critical tropes still feel right no matter how often they’re used. The staying power of the analogy is a lucky break. Not to retreat into cliches about critics being frustrated artists, but it’s not easy describing art when the (comparatively) successful artists themselves get in there early with “lightning struck itself” and “Vincent Black Lightning” (not to mention “Red hair and black leather, my favorite color scheme”). Birds, the weather, silver machines; all meager substitutes when we all know that none of us, on our best day, are going to top the imagery and accuracy of Verlaine playing guitar just like a-ringing a bell.

I can’t imagine what it was like for Tom Verlaine and Richard Hell when they were getting started; to have a weird voice, and wanting to sing for a band in NYC, without the advantage of being able to just rip off Tom Verlaine or Richard Hell. What were the options? All the geese were uptown in Central Park, and neither Verlaine nor Hell strike me as the picnicking types. Obviously the 13th Floor Elevators were a roadmap, but neither men were inclined to psychotropic blues howling. And it’s not like the radio was playing a ton of songs by the Lollipop Shoppe. Instead they had to make do with the screech of subway brakes, Skip James records played at the wrong speed, the sound of their own weezing as they crossed the 5th floor mark of their East Village walkups. As far as I know, neither singer was influenced by living with a cat.

The Family Cat, a UK indie band, put out a single in 1989, entitled “Tom Verlaine.” But–as is apparently the style when it comes to describing our hero–the song is more about the songwriter than it is about whether or not Tom Verlaine ever owned a cat.

Regardless, both Veraline and Hell found their way through their own respective keening. Verlaine’s voice was the more lovely of the two, playing the rose to Hell’s prick, but if neither had had the other, who knows? Maybe David Byrne would have ended up as the photography professor with the biggest suit in the history of RISD. Or he’d formed Talking Heads regardless and maybe all us pale imitators would have had nowhere to turn but to him, and maybe the Modern Lovers. A student of speculative fiction can only consider this wide-eyed alternate timeline, remorseless in its childlike wonder, and shudder.

The lyrics of “Prove It” allude to working on an unspecified case, quote the television show Dragnet in the chorus, and uses typically whodunnit imagery (proof, unreal nights, clocks and water) to hint that the song isn’t interested in any mystery that might be so easily resolved. As asides of indeterminate weight, Tom Verlaine sings, “the word’s just a feeling you undertook,” and “you’re in so deep that you could write a book”

Eight years after Marquee Moon came out, the author Paul Auster–possibly unaware of Verlaine’s challenge–published City of Glass, the first of the New York Trilogy, a series which makes uses of the architecture of detective fiction to communicate–as far as that goes–the impossibility of resolution, the illusory nature of either fiction or fact (I’m not really sure), and what the critic Ted Gioia called, “the futility of words.”

There’s a parallel to be drawn between the two works. If it hadn’t been over two decades since I’ve read The New York Trilogy, and I wasn’t a bit (happily) confused by the books even at the time, I would attempt to make that parallel clear. And undoubtedly reap financial rewards beyond my imagination.

Things being what they are, I’ll simply content myself with the knowledge that neither piece of art makes an argument for clarity as an inherent virtue. As Iris DeMent sang–with all due respect, I’m sure, to both Television and Paul Auster; “I think I’ll let the mystery be.”

The other notable aspect of “Prove It” is that–at about the 1:50 mark of the stop-start pastoral–Verlaine finally lets those goddamn bluebirds into the studio to have their own say. With a passion that I suppose could be described as inverted if that’s how one chose to think about a bluebird’s passions, the birds sing “chirp chirp.” But they only do so after Verlaine “chirp chirps” first, so it’s hard to know whether they intended their contribution as a co-sign of Patti Smith’s transcendently blurry praise, a commentary on the futility of language, or just the usual gossip and slander that bluebirds would throw on every track if we let them.

In an interview, Richard Lloyd quotes John Lee Hooker’s guitar playing advice; “Take off all the strings but one and learn the one string up and down and down and up and bend it and shake it until the women go ‘oooo.’ Then put two strings on and learn two strings up and down and down and up.”

In Dean Wareham’s Counterpunch essay about Tom Verlaine, he describes the minimalism of Verlain’s studio rig. “...a small case filled with vacuum tubes, a Fender Stratocaster, a green Guild Starfire hollowbody (with the Dearmond single coil pickups), a no-name electric 12 string with a high action that I found completely unplayable,” Wareham writes. “And a small amplifier that someone had built for him; Tom knew well that the right amp is at least as important as an expensive guitar. There were no effects pedals, no bag of tricks, only a pick, his fingers, and his controlled use of the guitar’s volume knob to achieve his unique sound.”

I don’t really know, on a practical level, what either of these quotes mean, outside of saying that Television played the notes that were needed to be played. I’m a lead singer, with the emphasis on “lead.” I help carry amplifiers but I otherwise mind my own business. I’m not interested in mechanics. For me, the “1” in a time signature is whenever I start singing. In a case of observation that perhaps says more about me than Verlaine (or Lloyd); until Verlaine died, it never once occurred to me that there were guitar solos on Marquee Moon. It never occurred to me that it was an album that could be parsed. I don’t know that I ever even imagined that it was an album that was written. I figured it was more like a weather event or something everyone who ever lived in NYC (or ever wanted to) was born with. Even on “Torn Curtain,” with its rising/converging guitar line, that’s railway spiked–barely in place–by the ghostly backing chorus of “years/tears,” I didn’t hear the sound of effort that might accompany humans existing in an outward fashion. I wouldn’t have guessed that there were musicians involved at all, if being a bartender in NYC didn’t require being told the minutiae of the lives of anyone who’d ever used the CBGBs toilets even once. As all the threading guitars snaked and dog-fought themselves into my DNA, I didn’t know there was consciousness behind them; I just thought that was how the song went*.

*The original version of this ended with "I just thought that was how the song went; the lightning being itself, the mystery just being." Upon a day's reflection, the last two phrases feel... a bit much. But I can't decide. So, if you're more on the "screaming bluebirds" side of the aesthetic divide (I go back and forth every other minute), please feel free to pretend the essay still ends that way.