Yeah Yeah (Yeah), Cool Cool (Cool): Fever To Tell at 20

The Personal Stuff

Regarding Fever To Tell, the debut long player released by New York City’s Yeah Yeah Yeahs in 2003, I have my biases. My feelings for Fever To Tell will always (I hope) be tied up with my friendship with YYYs’ guitarist Nick Zinner, who—along with my wife Zohra Atash and the artist Nate Turbow—has been a consistent source of joy in my NYC existence/existence in general. Also, my memories about Fever To Tell are tied to aspects of my artistic career that have been sources of… something other than joy.

About my friendship with the YYYs, I don’t have much to say. I consider Brian Chase a friend as well and, while I wouldn’t be so presumptuous to claim friendship with Karen Orzolek, I’m personally fond of her and I like to think that fondness is reciprocated. Beyond that, I keep my friends (of varying degrees of fame and/or friendship) by not using them as source material in my writing. I understand that this principle, of not running over one’s grandmother for a good story, might be anathema to those who consider themselves “real” writers. But I figure I can mine enough material from reading, my imagination, the awareness of human nature that is the overripe fruit of a lifelong self-involvement, and my penetrating and incisive—and objectively correct—understanding of each and every underlined name on an enemies list that’s long (and getting longer).

If Zinner and I ever have a falling out, I might reconsider my approach to Yeah Yeah Yeahs journalism, if the price is right ($1,000,000, to be paid in Camel Cash). But I’m afraid any tell-all would make for dull reading, with the worst thing the guitarist ever did to me being him not taking enough care to keep the other NYC-in-the-Aughts Zach, the singer of Seconds, from snagging my list spot at the Brownie’s YYYs/Milemarker show. I’m clearly still mad about that slight, but not so mad that I’m ready to invent flaws regarding someone who’s as sweet a person as having the nickname of “lil’ vampire*” will reasonably allow for.

As for the aforementioned deficiencies in my artistic career, those are part and parcel of time passing, and choices that I (and some foolish/blind label A&R guys) made while it did. If the reader wants to blame “luck” or “politics” as well, they should fee encouraged to do so. What’s left; what wasn’t a choice, luck, or politics, was the unfortunate cost of what can most generously be thought of as a *cough* late blooming charisma.

I realize that many of my contemporaries made art because of a deep and undeniable calling, with zero concern for the vagaries of fame and fortune. I made art for the thrill of it, sure. If not necessarily for its own sake, then at least for some other esoteric sake. But I also wanted to be praised, and for that praise to be delivered as both money and attention. Instead I got three mentions in Meet Me In The Bathroom, one of which was the Strokes manager saying about my band of the time—when recalling the YYYs’ first show at Mercury Lounge (where they played right before us)—something along the lines of ”remember that band?”

Regardless of the cause, I sum up that period in the same way I always have. Have you seen that Charles Adams New Yorker cartoon; where a unicorn is standing on a rock—in the pouring rain, with water rising high around it—while Noah’s ark floats away in the distance? That’s what it felt like watching my friends get famous.

As for any life regrets that might be directly connected to Fever To Tell, there aren’t any that couldn’t be just as easily attached to Is This It or Turn On the Bright Lights. When I stare at my cats and consider which of my famous friends’ successes I took most as a divine indictment of my own lack of talent and/or character, the YYYs are indeed my go-to. But one could make the argument that my having served alcohol to The (at the time underage) Strokes at Mars Bar—and having opened for the band at Mercury Lounge—makes Julian & Co. worthy of at least a degree of jealousy-tinged reverie. And my having briefly been Sam “Interpol Drummer” Fogerino’s beleaguered wingman qualifies Interpol’s debut for the same rueful distinction. Conceding that, Fever To Tell is the album—of the New Rock Revolution Big Three debuts—which I return to, regularly. With any associated pangs of envy far outweighed by a genuine pride in just being peripheral to its creation, and by the undiminished thrills that, two decades later, the album still provides.

All the above leads to a question. With loyalty prohibiting any literary weaponizing of my friendship with the YYYs, and with the disappointments that accompanied the time largely erased—more than mitigated by the salve of aging, a hot and brilliant wife who I love more than I have ever loved anything (including cocaine), and the fact that I am currently more famous than any band that Kanine Records chose to sign instead of me—what is there left to discuss, on this Twenty Year Anniversary of Fever To Tell?

The music? In an Anniversary Piece? I’ll give it a whirl, just this once. I guess this is what Blink-182 were guessing when they said, “I guess this is growing up.” Of course, if Blink-182 had guessed that wisdom to the tune of “Y Control,” they would have sucked shit a lot less hard. That’s their choice to regret, not mine.

The Music

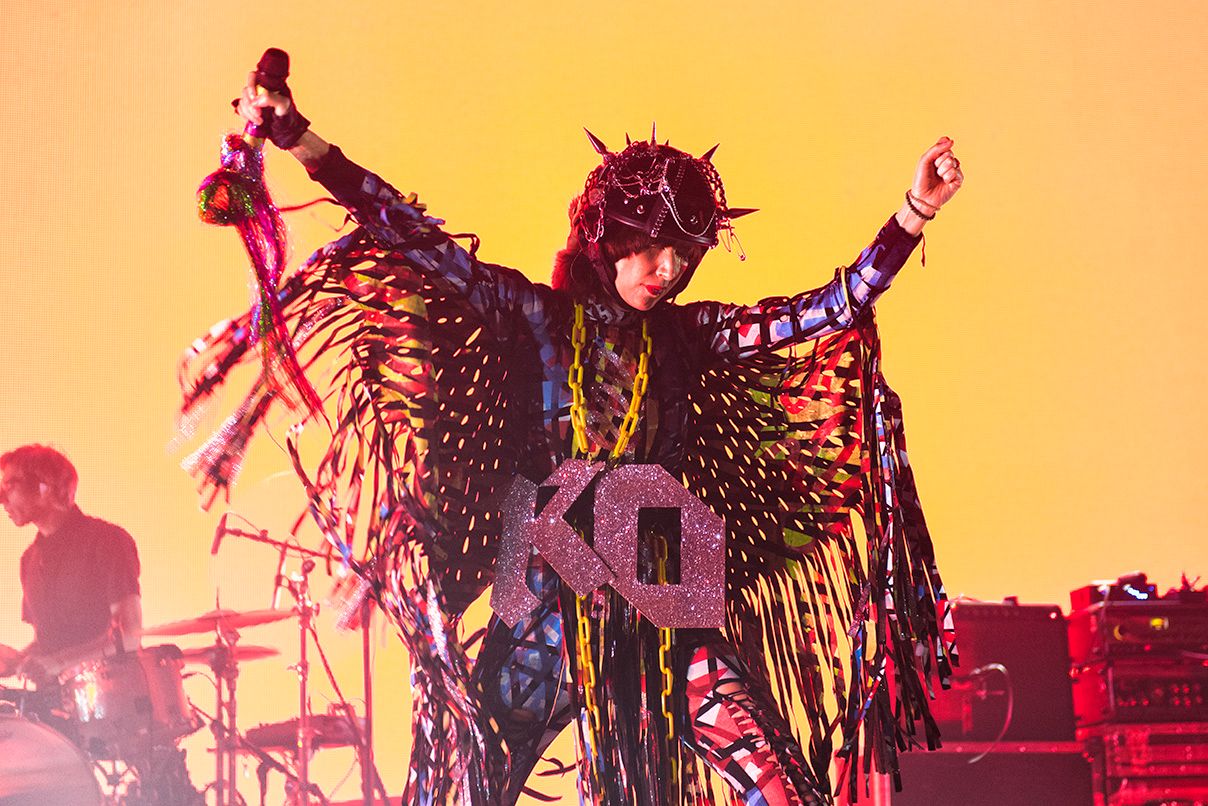

First, the fact of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ music being “pop” popular is a miracle. Even the committed YYYs hater should consider the details of the band’s sound (even if the poor misguided hater can’t stand it), and they should consider how improbable it was that those details might add up to commercial success. Dismissers and faint praisers might focus on “flamboyant chick acting all crazy and pouring booze on herself, during one of the periodic peaks of the perpetual garage rock revival.” They might then—with hindsight being as blinkered as any sight—feel justified in smugly seeing the band’s popularity as a foregone conclusion.

But, conceding that Karen O’s outsized personality played no small part in what would come, consider this as well: a bassless trio, fronted by screeching and sneering film student, who refused any coverage that focussed on her at the exclusion of her bandmates. Consider a guitarist with a Birthday Party hairdo and a pedigree in hair metal fandom—whose riffs were only “garage” loosely, being more likely to alternate between the razor burn of China Burg and the impressionistic spray of Kid Congo Powers, and whose blues gallop was less White Stripes doing “Stop Breaking Down” and more Slayer doing “Necrophobic.” Consider a drummer who name-checked Buddy Rich, held his sticks in the “traditional” way—like he was raised real proper and his kit was a bowl of fancy soup—and who used the snare as an accent to whatever oblique four-on-the-floor beat is presumably played in Dharma heaven.

Then consider this trio treating garage rock like the genre’s archetypal band wasn’t, say, The Sonics. Instead operating from the possibility of an alternate timeline where the Chrome Cranks wrote Chairs Missing, and that album traveled across dimensions and was left outside the door of Karen O’s Oberlin dorm room, so that, a few years later, Cranks singer Peter Aaron’s LES-light-polluted-moon-howl and Wire’s “I Am The Fly” looney-tunage could be used as a template. Consider that band, after they added nearly every note played/not played on No New York to a Long Island Iced Tea that the members drank to excess from at every show, becoming as popular as The Strokes and Interpol; two bands who, whatever their flaws or merits, made music that’s popularity—considering the time, and the fact that, by 2002, the Velvet Underground (or Tom Petty) and Joy Division (sorry.. The Chameleons) were hep cat consensus favorites—was considerably more predictable. Rather than recreating music that, via college radio, was practically classic rock, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs took the beloved-more-in-theory-than-in-practice chaos of No Wave, and they velvet-ly hammered it into something close to a pop song form, with no shortage of serration intact. And the kids went bonkers for it.

Maybe, maybe, maybe the kids were suckered into liking it because the songs carried the freight of potential sex, a potential scene, and the promise of horizontal stripes n’ sweat, NYC below 14th Street credibility, and upskirt bohemia. Maybe. The heart can be a sly and secret (occasionally double) agent. But if that’s the case, the kids unwittingly drank down a bucket of avant-garde medicine underneath all that sugar. Maybe that doesn’t add up to a religious miracle but, considering that cool-esque kids eventually retreated into the status-quo-laundering placebo-rock of The Killers and Kings of Leon, the fact that the YYYs ruled the radar even briefly was some sort of victory for anyone who ever knelt at a shrine to Teenage Jesus & The Jerks.

Not to belabor the point, but to insist that it’s a point worth working; aughts nostalgia has done a disservice to just how strange the Yeah Yeah Yeahs were (and are).

I’m not sure when the historical misremembering started. Probably around the time Is This It came out, and both the counterrevolution and the New Rock Revolution itself started seeing cokedealer and/or model fucker in every cupboard. Regardless when the notion started, that all the NYC bands existed solely to do lines of Tower 7 dust—with both musicians and fans prioritizing pastiche and party photography over True Art—this narrative, when applied to the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, depends on a particularly aggressive brand of misremembering. Because, even at the time, the YYYs’ disinclination to be pigeonholed was taken as a given. Nearly taken for granted. While, yep, the YYYs certainly did tour with White Stripes, the first couple bands to take them on tour were Girls Against Boys and Jon Spencer Blues Explosion. They played multiple shows with post-hardcore bands like Milemarker. Not that any of those bands were so crazy, but they collectively speak to a diversity of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ “scene” that strays from the “indie sleaze” narrative. While the press quickly grouped the band in with the acts that moved similar units, and aughts nostalgia has codified this story, YYYs were more likely to be playing with Brooklyn psych and noise-adjacent bands (like ex-models and Rogers Sisters) as they were with any of their fellow beneficiaries of any larger hype. Their primary peers were Liars and TVOTR; two bands that shared the YYYs’ inclination for making the avant palatable, without any of the three being overly concerned with sanding the music’s edges beyond Trojan Horsing the oddball sounds into (relatively) conventional song structure. (Obviously, of the three bands, Liars were even less interested in any sanding of edges… though they would eventually return to some of songcraft’s simpler pleasures…)

In fact, looking over the YYY bills of 2002-2004 is like scanning a chronal map that begins with the last gasp of Touch & Go as a primary force within indie, and shifts into the onset of the bananapants confusion of mid-aughts underground, which allowed for bands like The Locust and Blood Brothers to reach mass audiences. In between, the usual white blues or indie time capsules (like the sadly unsung Ikira Colt and the… unsung Soledad Brothers) do pop up (not to mention VICE detritus such as DFA 1979), but they’re in the minority compared to the number of acts that few would associate with even the scattershot and expansive, complete smudge of Early 2000s ahistorics that is how the time is currently recalled.

Before the YYYs, Nick Zinner had been in a band called Challenge of the Future. That band (which formed at Bard College, under the name Boba Fett, and whose singer would go on to front the excellent art-klezmer outfit, Golem) put out one album, Everyone Everyone Everyone, in 1999. They played a kind of dub-influenced, Sabbath-y take on Roxy Music’s artistically sleazy grind and digression. The music was good and all the girls at Sweetwater Tavern had crushes on Challenge of the Future and the member’s gravity defying hair. Unfortunately, there was a limited audience for stoner-glam, and Jonathan Fire*Eater had already called dibs on aristocratically pleasing hairdos and cheekbones. So CotF broke up, leaving Zinner’s talent—for riffing doom-inflected air sirens and for rendering Misirlou from a shark’s point of view—without an outlet. I can’t remember how he met Karen, and I’m not looking it up. But he and the nascent songwriter—who up to that point had been making movies about anthropomorphic mice being slaughtered in their Manhattan apartments by duplicitous cat-people—did meet. Presumably at Shout; the soul night on 13th Street where most bands that weren’t formed in college, formed.

The oddness of the music of the YYYs was apparent in Zinner and O.’s earliest collaborative efforts (when they were a duo called Unitard, playing perverse proto-shitgaze folk songs in the backroom at Sidewalk Cafe) and would be most pronounced on the metallic knockout-ism of 2007’s Is Is EP (and arguably on their second album, 2006’s Show Yr Bones, which is both my favorite of their catalog, and was understandably a bit confusing to those who wanted Fever To Tell 2), but there’s plenty on the band’s debut that showcases the band’s alchemical fusion of far-afield garage-punk, surf-thrash, and haunted house ESG energy.

These days, the first YYYs EP (which was self-titled, not called Master apparently) may sound (compared to what came later) a bit like a historical curiosity. But, if that’s true, the songs are worth being curious about. The final full minute of opener “Bang” has the band fucking around with keyboards and canned handclaps, as if they were still listening to the Jon Spencer experimental remix album and wanted to make sure there were enough groovy stems that whoever was the Williamsburg equivalent of U.N.K.L.E. had enough to work with. “Mystery Girls” is a charming dream of the Cramps signed to Kill Rock Stars. “Art Star” was the first clue provided by the band that they weren’t going to be content to play the garage revival revival circuit. “Miles Away” is a first draft of “Machine,” an early indication of the band’s capacity for gothic melodrama. And, finally, the EP ends with “Our Time,” the song that would prove to be the “My Generation” for everyone who dared to defy the societal norms of only wearing one belt at a time. I’m not prone to over-crediting artistic intent, and am not presuming to grant Karen O. any fortune telling ability. But I can say that she was always smart as hell, with the level of bravado and self-awareness required to write a song that might intentionally be both attuned to a band’s potential place in history and take into account the accelerated cycles of love and backlash inherent to an inwardly-collapsing culture. And there’s no question that, to those who got the Yeah Yeah Yeahs CD when it came out, both the bravado and prescient valorizing of being hated seemed earned.

Fever To Tell often builds from the scuzzy bones of the EP. The band’s debut just as often ignores those bones entirely. While, in infernal retrospect, it’s easy to take Fever To Tell as mere zeitgeist embodiment. That assessment is neither unreasonable nor accurate. First off, regardless of what some historians might insist, none of the YYYs were cokeheads. I know because I’m still annoyed at the number of times the members declined my generous offers to share my drugs. There was undoubtedly dabbling, and some time spent at Kokies—the salsa club/afterhours on North 3rd which served as a late night/early dawn club house for even the more drug-averse scenesters—but the album was recorded sober. Sorry, hagiographers of the party photographer era. The strychnine sinew of the songs, the last-bar-fly-standing thematic sluttiness of the album, were the result of its members being in the throes of improbable possibility, not literal drugs. The band—in love with NYC’s gutter-rock traditions, the skronking blues of the better garage-noise around them, and possibly each other—wasn’t high. They were just spiritually messy.

The Part Where I Compare Yeah Yeah Yeahs To Helmet (feel free to skip)

If we feel like following this path of sobriety to an illogical conclusion (and you know we do), there’s an almost hysterically puritanical album, from a decade previous, that Fever To Tell might be compared to. Rather than Fever To Tell’s seemingly obvious forebears—debauched fuzz strutters like The Cramps’ Bad Music For Bad People, or anything by the sexual/spectacle healers in the Make-Up—there’s a third, counterintuitively austere, option.

Arguably (if it even needs to be said), the from-the-gutter, NYC-trad-enamored, rock and roll album that Fever To Tell most closely resembles is another notable NYC success story. An album, by a similarly LES-‘82-indebted outfit, that was also improbably embraced by both critics and the public at (very relatively speaking) large. I am, of course, referring to Helmet’s 1990 debut, Strap It On.

If this seems ludicrous, no, it’s not. You are. Or rather you’re free, and you just don’t know it yet. So you’re holding on to the psychic prison bars of your youth. But, my friend, there are no bars. The prison guards, those dream police who smacked your face every time you dared even broach the subject of early Yeah Yeahs Yeahs’ tonal similarities to early Helmet, are gone. If they were ever there in the first place.

Even if Strap It On and Fever To Tell don’t sound alike (though they do), the two albums are—If one visualizes shapes while listening to some music— shaped alike. Strap It On and Fever To Tell are both rough hewn blocks of song Lego, with Jenga towers of repeating riffs, with singer and drummers alike repeatedly enlisted as apparatchiks and enablers to the rock tumbling, road-crew repetitive cycles of—ceaselessly played as—rhythm guitars, with shrilly acute guitar angles thrown over and under the verses, as each bands’ front-people yelp and croon oblique conjurings of back alley disrepair throughout.

While Helmet drew from hardcore and Yeah Yeah Yeahs drew from garage, both bands approached those genres with only the minimum amount of reverence required to win over fans of the respective sounds. Importantly, both acts studiously avoided any of the Civil War reenactment tendencies of so many specific-subculture artists—with Helmet eschewing both hardcore’s varsity jackets and the affected poverty of noise rock, and with YYYs declining garage rock’s mandate to dress like either Brian Jones or a gas station attendant. Therefore, rather than being trapped in a single scene—surrounded by all the aesthetically thick fanatics who might hang around any particular trap by choice—both bands were free to choose their own friends. And, while neither band was concerned with slavishly worshiping—or petulantly bucking against, which can often feel like the same thing—the tropes of hardcore, metal, or garage rock, both bands went further; approaching the avant-skronk/no-wave (which both bands loved) as something to be bullied. To be shoved into a pop-structured locker just long enough to fit your average Ramone.

What unites Strap It On and Fever To Tell is, within the confines of “logic” or “any interviews where either artist even alludes to any kinship,”, hard to argue for. But, setting aside logic and evidence, the comparison feels true. Two albums of vigorously economy-minded songwriting, sharing a more-than-passing familiarity with the Glen Branca songbook and a profound understanding that Sonic Youth might be better if they grooved a bit, and with both albums chiefly concerned with pushing in the pin, whatever that might entail (in this case; two gangs of fanatical downtowners playing “The Hair Shirt” from different angles). If either band chooses to deny this kinship, I’m going to need it in writing.

Caveats:

- It’s doubtful that Helmet’s drummer utilized the classic jazz hands, but I bet Page Hamilton holds his guitar like Brian Chase holds his drum sticks; like a classical conductor placing one movement in front of the other.

- Obviously the YYYs were better dressers tha Helmet. I’m just saying that both debut albums have surprisingly similar auras.

- tbc I’m speaking exclusively of Strap It On. The Born Annoying 7” and the Meantime LP are both still fun. But, from their second album on, Helmet’s metallic sheen would only become more pronounced, with a span of influence that would eventually result in Snapcase and the ruination of nearly every hardcore album recorded for the next fifteen-twenty years. Not their fault, but not not their fault either.

- It’s not terribly likely that Karen O. had intentionally listened to Helmet once in her life.

- When writing the Branca and “Sonic Youth might be better if they grooved a bit” line, I almost added a part about how both bands performed a funky take on other notable LES denizens, with Helmet rendering the Swans’ sound as reggae and YYYs rendering it as ska. But I don’t feel like having Zinner (or Gira or Hamilton for that matter) mad at me. Plus I thought of where going further down that path would lead, the Prong or Railroad Jerk comparisons I’d eventually have to make, and all of a sudden I felt very sleepy.

The Lyrics

Like the better stupid/smart lyricists (such as Amy Taylor or Lemmy)—who decline to sing quasi poetry, straight diary, self-congratulatory gestures towards profundity, or any universal didacticism—Karen O. is underrated as a lyricist. What’s often dismissed as crudity or merely provocative wordplay is, just as often, swaggeringly intuitive renderings of human condition/pain/horniness. Karen’s lyrical skill would become more evident on Show Yr Bones (“there was a crowd of seeds… I must have done a dozen each”) and 2009’s It’s Blitz (“dripping with alchemy” etc.), where she would balance her party-at-the-end-of-time persona with a more explicit romantic/absurdist existential angst. Karen’s lyrics on Fever To Tell are more of the Little Richard school, with the singer shamelessly indulging in an a-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-good-God-damn!-style of emotional shorthand. Specifically in the “Bam, bam, bam, bam, bam, bam, bam, bam, bam/Duhduh, duhduh, duhduh, duhduh” of “Pin.” And more generally in… almost every other song, where she repeats single-syllable words well past the point of repetition, until words like “rich,” “tick,” and “choke” become divorced from language entirely, and become as evocatively absurd (or as much coded references to taboo sex) as any early Rock and Roll rave ups. This could be taken as lyrical laziness, and certainly has been taken as such by not unreasonable critics, but when one considers the brilliance of the YYYs name itself (partially a tribute to rock’s most notable contribution to linguistic multiple-meaning signifiers, but also a salute to the New York tic of showing approval by saying “yeah yeah, cool cool”) it’s clear that the way, in which meaning is sometimes best communicated via nonsense, was baked into the Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ since the band’s inception.

Even if Karen O. was still feeling her way through lyric writing—still getting her leather on, as it were—there are still plenty of words on Fever To Tell to admire. Especially for those (like me) who prefer Stooges-ian evocation like Amyl & The Sniffers’ “Some mutts can't be muzzled/I guess I got you puzzled/Woof, woof!” to the dire genius of, say, The National (or Father John Misty or Bon Iver or whoever). A sample Karen lyric, like “Boy you just a stupid bitch/And girl you just a no good dick,” from “Black Tongue,” is fine enough; an underappreciated subversion of tropes during a time when both the indie world and the nascent and excruciating pomp-pop-punk craze was interested in gender swapping only as a eye-shadowed beard for describing girlfriends as crazy cunts. But there’s also the simple-spell/complex-conjuring of “we’re sweating in the winter” and the album thesis of “I said we're all gonna burn in hell/'Cause we do what we gotta do real well/And we've got the fever to tell,” which serves as a scene’s warcry nearly as well as “our time to be hated.” In other places, Karen O. focuses exclusively on the heart; with “Modern Romance” and “Maps” being the resultant album tentpoles. I’ll cop to “Modern Romance” being my least favorite song on the album, and potentially my least favorite in the band’s early catalog. I don’t dislike the song (and I understand why others find it moving). But for the same reasons I find her more oblique howls so effective, even if the heartfelt emotionalism is used to confuse what the song’s intent might be (which is interesting!) I still find the song’s directness (even if it’s an inverse of what’s stated) a bit too on the nose; too unstrange.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oIIxlgcuQRU

Not so with “Maps.” That song, direct in its fashion, works like a motherfucker.

If, on other songs, Karen O.’s use of lyrical repetition serves to achieve a primal, beyond-language rock-lexiconical potency, the singer takes care to do the opposite on “Maps.” Every line’s meaning is maintained, each imbued with a spurned lover’s (deluded) belief in the power of debate to change someone’s feelings about them. Each “wait” or “they don’t love you like I love you” isn’t a separate thought, exactly, but they are sung like they might conceivably build on each other in a coherent argument, with which the singer might—somehow, against all other logic or evidence—still get what they want.

The Music, Part 2

Musically, “Maps” is made of only a few elements. It’s got Brian Chase doing a glacial take on a Kevin Haskins-style Bauhaus beat. It’s got Karen O. spelling out her plea. And it’s got Nick Zinner alternating between pointillism and cascade on his guitar. The pointillism is arguably the needling (sorry for the mixed metaphor) thread that makes the song. Like Glen Campbell’s rendition of Jimmy Webb’s immortal and perfect “Wichita Lineman” (another song with no more parts than necessary), “Maps”’ message is driven home with a telegraphic punctuation. If the guitars on “Maps” bend a bit more than the tremolo-bass-and-strings morse code that the Wrecking Crew’s Carol Kaye came up with for “Wichita Lineman,” the effect is similar. Karen O. repeats her version of “and I need you more than want you/

And I want you for all time,” while Zinner and Chase both underscore and illustrate the inevitability of inclement weather.

Before ripping “Maps” off, Max Martin famously bemoaned that the song only lacked a chorus. Martin has probably never read Greil Marcus’ essays on “Mystery Train” or “Eight Days a Week.” If I remember correctly, Marcus argues that both songs’ power partially resides in their refusal to resolve in an entirely satisfying fashion. Because, you know, no great rock and roll comes out of getting satisfaction. Rock and Roll is, perhaps counterintuitively, more about tension; about not being able to get what you want. Top cogs like Max Martin don’t really “get” tension. They only understand release, with imaginations that can only operate as vehicles for attaining a happy ending (in both senses of the phrase), and they make very successful careers based on satisfying the public’s need for constant, undeserved reward. Not that “Since U Been Gone” is a bad song. It’s not. For what it is, it’s great. But what it is—like most art designed for industrial use—is a brutalist idea of beauty. Which, again, is still beautiful. But it is as impenetrably smooth as “Maps” is fragile; 90% gilding and 10% lily.

I might feel differently about “Since U Been Gone” if I had been in the video for it. But, in the absence of time travel, Kelly Clarkson will just have to read this newsletter with an ache of what might have been. (Yes, this is my way of saying I’m in the video for “Maps.” at least the back of my head is. At least I think that’s me. I was there, but I’m not actually sure I made the final cut. If I didn’t, director Patrick Daughters—in regards to my eventual place in the Meet Me In The Bathroom narrative—was ahead of the curve.)

Let’s Wrap It Up

Regular readers will be aware that I don’t put much value in individual works of art (or musicians) being “important.” Not that I don’t think art matters, but I figure that being overly concerned with legacy and influence is a small leap away from diving headfirst into worrying about hierarchy. If some art is important, then some art isn’t. And, while that may be true, I prefer to leave that whole debate to the Objectivists, Incredibles, and all the other mongers of assigned-by-aesthetic-merit decimal points. If The Strokes’ success resulted in half the youth population of the British Isles to start cosplaying as male models for an endless Details Magazine ad campaign for Tom’s of Maine and/or intravenous drug use, and the YYYs only directly led to Morningwood being briefly viable, so what? Conversely, if nearly every indie female-identifying front person for the last two decades has used Karen O. as a template (or as a template to be performatively rejected), and every guitarist to play from two boxes of boom (I don’t know tech stuff) owes Zinner (and, depending what history books one reads, Jack White and/or Jack Martin) a debt of gratitude? Also so what. Neither history nor its creative bootlickers have any bearing on any art’s value.

So what then are we left with; if both history, and history’s slap & tickle, are rejected? If I’m not even apologizing for my bias? If I’m arguing that songs have shapes and auras? Are we to simply succumb to our current era’s reliance on “just vibes”—a rational submission, considering the high number of debate fetishists who seem to be just looking for a way back into phrenology? Maybe so. Or maybe seeing Fever To Tell as a persistent anomaly—as an album that’s value exists outside of canonical concerns—is to appreciate the album’s place within a tradition that, at least ostensibly, was always looking for a way out of Squaresville. And therein lies some rhetorical danger as well. Fever To Tell does not fit neatly into any of the Rock and Roll subgenres. Like the band that made it, the album is too strange for garage, too abrasive for new wave, too eager to please for no wave, too trashy for post-punk, and has a relationship to punk that can best be compared to ex-lovers who don’t talk, don’t follow each other on social media, but who don’t wish each other any harm either. And, unless you’re comparing them to the Wedding Present or The Smiths, I’ll see us all in hell before I concede any friends of mine as “indie.”

So, what’s left is Plain Ol’ Rock and Roll. The stuff Bob Seger sings about. But Fever To Tell deserves better than that broad and complimentary, too easy, and admittedly tempting, placement. At this juncture—with every year that passes another year that the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame hasn’t been burned to the ground—is “they’re just rock and roll, man” even a compliment? While I understand that any band that had an issue with existing within an ill-defined Rock and Roll landscape probably wouldn’t have named themselves, three times, after the genre’s favorite word, I’m still not quite prepared to hand such a peculiar band over to “rock energy” historical fog, as if the trio were just an edgier Goo Goo Dolls.

I have no good answer. To this question, which admittedly no one else is asking. I suppose Fever To Tell will remain what it is; a perversely admired freak, misunderstood by design. Which is where so much of the album’s appeal resides; within the realm of the positively unlikely, where odd looking kids can get by on weird winks, a winning ability to be too forward without scaring anyone off, and a solid record collection. Where “you look like shit” sounds a lot like a pick-up line, where they play The Birthday Party at discotechs, where discomfort hints at a growing possibility, like sweating in the winter.

Thanks for reading! Buy the new YYYs album! Subscribe and share this newsletter! Subscribe to Creem! Buy Zohra's album! ty ty ty!