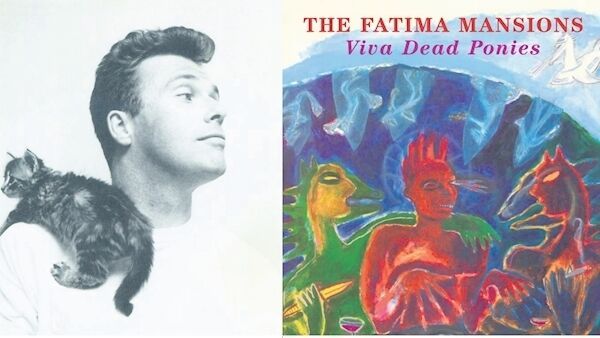

Viva Dead Ponies: In Memory of Cathal Coughlan, 1960/61-2022

I was shocked to read that Cathal Coughlan died, but not because he seemed young, or because he’d ever given the impression, like Lemmy or Bowie did, that he’d live forever. Coughlan, the former frontman of the Irish (specifically Cork) post-punk bands, Microdisney and Fatima Mansions, was a singer of the Angry Young Man school who seemed like he’d been a world-weary thirty-five since birth. And, while never vibing as old, Coughlan was such a lifelong acolyte of Scott Walker’s low-crooning, existential contempt that I’d frankly been surprised that he hadn’t, in a show of Seventh Seal chess-with-Death solidarity, packed it in the day his hero did. Or, preciousness aside, I was shocked because I never thought of Cathal Coughlan as a man at all. I thought of him as a collection of songs. Or, to be honest about my selfishness, I thought of him as a secret catalog, that only I knew about. And anyone who has internalized their fair share of Scott Walker’s fog-laden drama (i.e. anyone who has run Jacques Brel lyrics through google translate or who knows the lyrics to Tindersticks’ “Rented Room” by heart) finds it hard to believe that a secret might ever expire.

I’m romantic, but I don’t follow that inclination to its logical conclusion of being entirely delusional. I know that, barring the unlikely possibility that MTV’s 120 Minutes was an interdimensional wave of energy shot into my brain alone, Cathal Coughlan wasn’t actually a secret. Apparently there were entire countries where he was, for a time, reasonably well known. Upon the announcement of Coughlan’s (“peaceful, after a long illness”) death, deeply felt grief was publicly expressed by writers from The Guardian, John Doran of The Quietus, the Everything But The Girl singer Tracey Thorn, Auteurs and Black Box Recorder’s Luke Haines, and The Charlatans’ Tim Burgess. If any of them shared my solipsistic sense of ownership to the deceased’s soul, they had the good taste to leave that claim in their drafts.

For myself; I didn’t know Cathal Coughlin personally. I didn’t know his family. While I don’t wish even a moment of sadness to befall any former or current member of Everything But The Girl (let alone Marine Girls), empathy for an online stranger’s pain is often aspirational. Like everyone, but apparently Jesus Christ, I have plenty on my plate as it is. So, while again wishing for nothing but an alleviation of sorrow for Cathal Coughlan’s friends and loved ones, and while palpably hating and fearing death enough to–in scared fellowship–wish Coughlan had more time, I can only grieve the idea of the man.

As this is a newsletter that’s ostensibly more about music discovery than a constant recitation of how I’m crying into my cats’ fur on any given week, I’m hoping that I can convey a small aspect of the idea of the man, just some of his songs–the miniscule way in which his as-gigantic-as-anyone’s life touched mine–in such a way that the dead man’s living idea/spirit/art is contagious. If terror at the airborn is to be the default, don’t we deserve the occasional banger?

Fatima Mansions formed after the dissolution of Coughlan’s first band, Microdisney. On the strength of their first album, 1989’s Against Nature, and high buzz from the English press, the band signed to the American label, Radioactive Records, which allowed for some late, late night MTV exposure. I first heard Fatima Mansions in January of 1992, when I saw the video for "Blues for Ceausescu,” a stand-alone single, recorded after Against Nature, that was included in the stateside reissue of Viva Dead Ponies (the band’s second LP, originally released in 1990). According to the 120 Minutes archives, VJ Dave Kendall played “Blues for Ceausescu” in between videos by the Johnny Marr/Bernard Sumner emo-disco project, Electronic, and The Dylans. Kendall would play Nirvana a few videos later. College Rock had recently become Alternative Rock, and the 120 Minutes VJ, who was sporting a black leather jacket and still had a haircut styled to walk that fine line between Reid Brother haphazard and synth-pop coiffed, was doing the best he could.

Even in this confused context, Fatima Mansions stood out. The repetitive drumbeat was pure Killing Joke and the repetitive guitar riff was pure Ministry worship (Fatima Mansions would later cover “Stigmata”), but Coughlan, buggeyed and shaking under a billowing army jacket, was less pre-grunge shaman or Halloween biker on speed than a WW1 trench rat attempting to croon, bellow, and snear his way through shellshock. As alt music transitioned from cool/fey contempt to depressive tantrum, the singer of Fatima Mansions had the voice of a cabaret lotherio, and he used his showtune-range timber like he was entirely unhinged. Without sounding like a punk (exactly), a goth (exactly), or a Pacific Northwest howler (exactly), Coughlan operated within all those modes. He did so while most approximating a time traveling chanteuse on a mission to kill baby Hitler. Time travel being an inexact science, Coughlan had to live in the era in which he landed. So he made due, directing his venom at the low-rent despots who were available to be targets of his considerable antipathy. Ever adaptable, Coughlan made the condemnation of “Blues for Ceausescu”’s subject being a “false economist” sound as damning as the “baby raper” insult that precedes it.

Enthralled by Cathal Coughlan’s voice and demeanor (and beginning to suspect that using grunge fandom as a shortcut to being interesting might eventually start paying off in smaller and smaller dividends), and expecting an album full of tracks like “Blues for Ceausescu,” I bought a compact disc of Viva Dead Ponies. Expecting an album of politically minded, grabbed-from-headlines denunciation, and quasi-industrial rock mania, what I got was… not that.

Viva Dead Ponies is a decidedly strange album. To its credit, even now. Taking the least fashionable aspects of post-punk, heavy metal, industrial rock, and even a little rap, the end result is a burlesque pop-metal album that refuses to pander to even the future steam-punks that might have been conceived while it played in the background. It sounds like if JG Thirlwell loved Scott Walker and Kix exclusively, was commissioned to arrange Jesus Christ Superstar for the casio keyboard, and then got caught fucking the mixing engineer’s wife. Viva Dead Ponies features warm and warbling, chiming, and even occasionally plinking synth lines (sonic worlds away from the coolly minor key lines Kraftwerk gave Depeche Mode, and Depeche Mode then codified for every darkwaver since). Viva Dead Ponies features at least one stab at aggressively not alternative pop; “Thursday,” a Beverly Hills Cop-esque jam that implies a 1992 where Courtney Love died on the set of Sid and Nancy and Teena Marie took her place as Kurdt’s blushing bride. Viva Dead Ponies features multiple hair-melody-metallic (practically bubblegum) guitar solos (that were/are anathema to any “alternative” rock band that wasn’t Warrior Soul or Manic Street Preachers). Viva Dead Ponies features a number of instrumental interludes that range from operatic to preset. And Viva Dead Ponies features richly over-the-top (and richly placed on top of the mix) singing, singing which jauntily weaponizes the anything-goes, genre-hodgepodge, Bill Laswell ‘80s, and a healthy amount of Burt Bacharach proto-power-balladeering, in a holy war against fascists, The Church, and all the individuals who ever acted as the emotional equivalents of either while either dating, or otherwise interacting with, Cathal Coughlan. (And lest the contemporary reader not understand why that last part might have been confusing, please remember that the Scott Walker popular revival wouldn’t kick in for at least another decade.)

I am not being unkind to say that the record, in 2022, sounds dated. Because the record sounded dated in 1992. Rather, the record is near impossible to place coming out in any year, so the assumption can only be that it was made in some earlier, imagined, time when the band’s sonic choices might have made some sort of sense. Maybe the 1960s, in some alternate timeline where The Mighty Boosh is a documentary.

And does the album work? Well, obviously, like a motherfucker, it does. What about the above description doesn’t sound awesome? I didn’t understand much of it when I was sixteen, but when I was sixteen I thought Alice In Chains was the worst grunge band, David Lynch was as weird as art got, and that Afghan Whigs’ Gentlemen was a relationship How-To guide. What I didn’t understand was a lot. But so what. When the album draws to a close, Coughlan spits out (on the roller rink cowpunk of “Pack of Lies”), “I could have been important/if I’d been somebody else.” He follows that up on the next song (and album title track) by crooning, in the character of the returned messiah; “Viva dead ponies/come out and fight me.” I didn’t need to understand context, or theology, or anything at all, then, to understand, and feel in my bones, the full weight of eschatological and existential grievance contained and conveyed in those lines. And I still don’t.

I have to work at Creem tomorrow. I have to be there before noon, and I’m writing this at 5AM, because I am sad that the singer of a band I like very much died at 61, and I don’t want to sleep and see my dead parents in my dreams. I don’t see my therapist till Thursday, but neither I nor you need them to diagnose a clear case of projection. Which is something I’ve been indulging in a lot lately. A friend’s dog died recently. When she told me about his last day, how he ran to the vet who was to put him to sleep, tail wagging and plush toy in mouth, I ugly cried in a way that I haven’t for either my mom or dad. I was exceedingly fond of my friend’s dog, but the circumstances of his death and that of my parents is not something that needs conflating. Friendly as my parents were, it’s hard to imagine them running up to cancer or Covid with a plush toy gripped between their teeth. Neither of them, while certainly being enthusiastic in their respective joys, were tail waggers. But then, I can’t stop thinking of my mother saying goodnight via facetime, confident that she’d be getting out of the hospital the next day. So… maybe. I don’t share Cathal Coughlin’s rage at God’s seemingly fickle mystery, but, also, there are days (and nights) when “Pack of Lies” resonates more than I’d like. To be alive is miraculous. I believe that to such a degree that I don’t even sweat typing the cliche. But my mom, my dad, a sweet dog named Ellington, the singer of Fatima Mansions, everyone and everything else orbiting or circling; the smudging of the line between carrot and stick can certainly wear a slim-trim kid down.

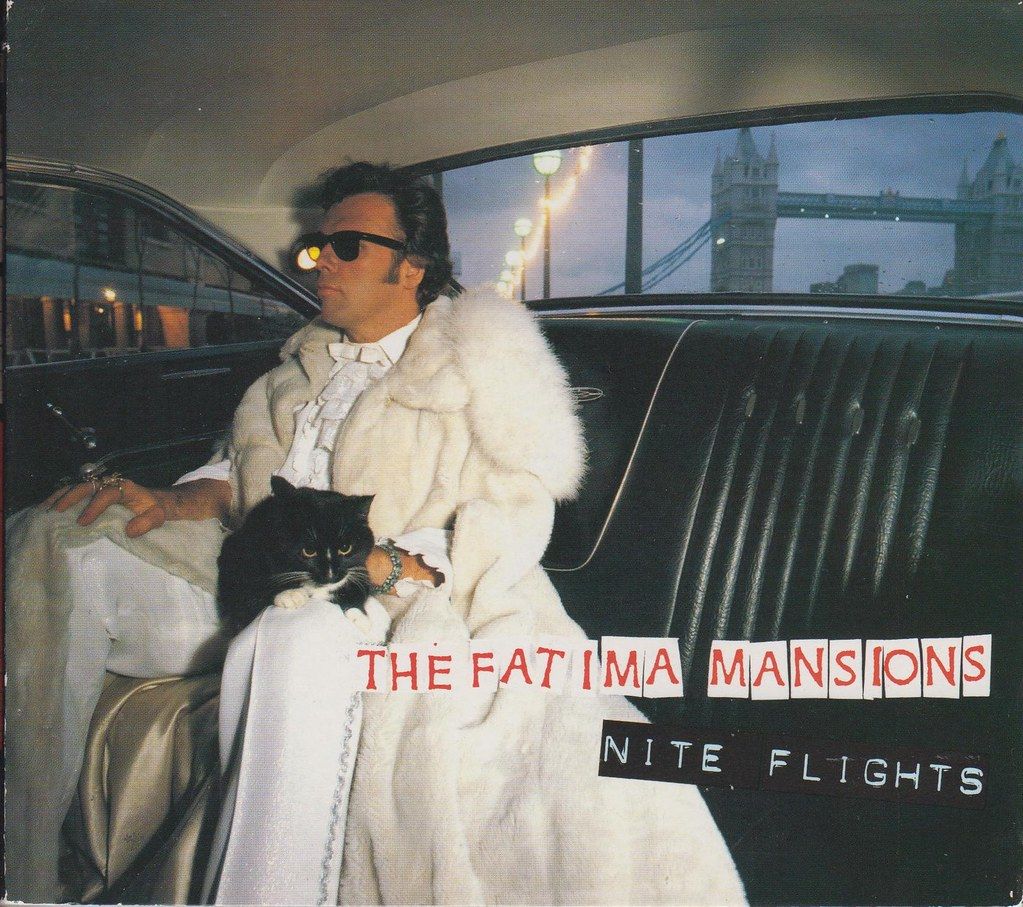

Post Viva Dead Ponies, Fatima Mansions did a couple more (very good) albums. Their last one, 1994’s Lost In The Former West, is particularly a pip. Probably the only album from the 1990s that encompasses the chunka-funk of Rage Against the Machine and the emo-grunge of Placebo, with a faithful cover of The Walker Brothers’ “Nite Flights” thrown in for good measure.

After Fatima Mansions broke up, Coughlan did a couple other projects that I haven’t heard, and a number of solo albums that were well regarded by The Quietus and The Wire (and me) and largely overlooked by everyone else. In the last couple years, however, it seemed like more people were coming around to Coughlan’s brand of acerbic observation, wry insight, and still gorgeous voice.

My dad, in the last year of his life, received a similar upswing in appreciation, but also his books have received more attention, in the months since he died, than they got in the last two decades combined. I hope the appreciation being paid to Coughlan now gives his family the small degree of comfort I feel by the attention paid to my dad’s last book. And I hope they’re more able than I am to withstand the rage that comes with the artist not being around to see it. Or maybe the rage is apt, and they should marinate in it. Probably, they shouldn’t look to me for advice. But of all the secrets that Cathal Coughlan revealed in the process of sharing his spirit, the moral/artistic imperative to turn a cheek to an overarching cruelty was not one of them. Nor was the idea that fighting against the tide might be ill-advised, in any circumstance, just because you’re a puny human/artist, and it’s the tide. Coughlan had a brilliant and unfashionable talent, and a voice as sweet and salty as anyone who ever paid rent in the L. Cohen’s hit factory. He was a man to those who loved him, a well loved idea to those of us who only had access to the songs, and he was as singular as he died too soon, just like everyone.