Laugh In The Dark: Aimee Mann & Ted Leo's The Both at 10

For those of us raised on the gospel of “The Velvet Underground & Nico's debut album only sold a thousand copies, but every person who bought it formed a band,” other people’s metrics for judging art can be frustrating. When faced with the argument that something we loathe is “good” because “lots of people like it,” we tend to react to the evidence of hard numbers like we’re Fredric March taking the stand in Inherit the Wind, and Spencer Tracy just told us that we’re descended from The Fame Monster. When pressed by a baggy-jeaned niece or nephew’s vocal-fried insistence that Billboard Charts are the only critic a person needs, some of us will pull up REM’s combined numbers and attempt to do some transitive temporal backtracking. The more savvy among our set might turn the tables and point out just how much Born This Way was “descended” from Madonna’s “Express Yourself,” and see how much the little fucker likes evolution now. Most of us will take the safest rhetorical route. We’ll simply channel the Principal Skinner meme. Are we so out of touch? No—in the question of, say, XXXTentacion’s merit relative to that of, say, the Dream Syndicate—it’s the children who are wrong.

Considering Stans to be wrong about everything is usually a solid bet. Stan culture—not to be confused with all the normal fandoms of the last 100 years (the teenyboppers, teddy boys, heshers, teenagers in general, teenage girls, mainly, in the specific, etc.) who make up the necessary foundation for any kind of popular music’s survival—is cruel and idiotic. If I’m being vitriolic it's because I feel strongly about Stan-dom as a societal force. I feel strongly that it is just plain rude for individuals—each endowed with their own miraculous essence—to sublimate that abundance into someone else’s myth. The fact that this idolatry comes cheap only aggravates the sin (and me). In the past, selling one’s soul to the Devil could get you gold, talking cats, or even rock and roll (with presumed first dibs on beating Jimmy Page’s ass when he eventually joins you in hell). Even in more recent times, with science allowing Satan to delegate, voluntary negation of the self at least came with a treat. Mr. Monopoly got a card for getting out of jail, the Nazis got to enjoy Paris in the Spring, and—on the other end of the spectrum—Maoism came with a spiffy cap. Nowadays, a confluence of spiritual, cultural, and economic deprivations—each one more inane than the one that came before—has seemingly made empty vessels of so many people that, not only will they join an online militia of end-time antinomians for free, they’ll gladly pay premium prices for the honor; announcing their joyful ceding of their autonomy by spending their adderall money on caps, shirts, and oversized hoodies which—in an entire perversion of the calls to worship elucidated by the Torah, New Testament, Quran, and Bob Dylan’s “Gotta Serve Somebody” —spell out, in the most tasteful Caelan Serif: “I Serve Cunt.” (The “exclusively, and at the expense of all else” is silent but implied.)

Still, as the original Stans (the Puritans) would tell you, nothing simplifies a debate quite like fire. If their larger views on art are symptoms of a mass-hysterical mental illness, Stans’ essentialist view of pop music—the dictum of “my god is bigger than your god”— has a certain steely clarity. While the rest of us waste our days—once spent in the noble endeavor of arguing over what is and isn’t “punk”—arguing about what is and isn’t “pop,” the Stans live free from muddle. In the way that God’s existence isn’t dependent on our belief, something similar holds for pop music. Call it whatever you want, as long as it sells. All that stuff that we call pop, that they’ve never heard of? That red dot you feel being lasered into the center of your forehead is a Mariah Carey gif.

For the rest of us, we can’t pretend that we aren’t choosing confusion. Not when the Allmusic biography of Game Theory begins with, “a singularly intelligent and imaginative pop band, Game Theory attracted little more than an enthusiastic cult following during their original lifespan of 1982 to 1990.” If a more expansive definition of “pop” is gaining as much ground as all the partisans of Carly Rae Jepson (and bands like the Smithereens or Too Much Joy before her) would like to believe, the juxtaposition between “pop” and “cult, would not be as jarring. Some wars just can’t be won.

Conversely, some artists—especially artists unconcerned with the doctrinaire tendencies of those music fans who’d maintain memberships in jumped up Mickey Mouse Clubs well into their twenties—don’t mind fighting a losing battle. While the application of the term “pop” implies one of the few metrics in art which can be verified via the market. There are still those who consider “pop,” especially when used as a suffix, a style unto itself. And they consider it to be one with a proud tradition of side-burned sophisticates on one end and fallow-period Charlie XCX on the other; one that’s varied sounds—Stereophonic to SOPHIE—are its own, divorced from the whims of a dum dum public (who only like what they’re told to like anyway). This way of looking at pop can feel like a cope when discussing Carly Rae Jepsen, when furiously typing away on some message board that Jellyfish would have been bigger than the Beatles if only people weren’t so stupid, or when considering what, given their druthers, the kind of success Material Issue would have preferred. But, if you aren’t looking to keep things any less complicated than any of the chord progressions on Lolita Nation—and the height of your financial ambitions are a house as big as Carl Newman’s, but no bigger—the term “pop” is yours for as long as you can hold it. And, within the context of things that don’t matter but still make life bearable, that’s a fight worth fighting. “Pop,” while undeniably aspirational, is such a great name for any type of art. It would be a shame to cede it entirely to the Dr. Lukes, Jack Antonoffs, and Max Martins of the world.

The Both, made up of two lead singers who sublimate only so much of themselves to make a girl-group harmony which sounds as sweet as sugar—play pop music. The kind of pop they play is “guitar pop,” and it once was indeed very popular, though not since Adam Schlesinger and Chris Collingwood predicted the PornHub narrative golden goose (the old/young/family/ick part of the goose, not the trafficking part). Or, really, even before then. Before even the late ‘90s picking of Everclear’s bones ensured that whatever movie Seth Green might be smirking his way through at the time had enough bleached-tipped grunge or white bread funk to fill a CD soundtrack. In fact, to find an era where the specific branch of power-pop-rock that the Both focusses on—paisley overground guitar rock, leavened with harmony and lilt—was popular popular, you have to go all the way back to when the Gin Blossoms got rich off the ghost of their friend they’d kicked out for achieving, paraphrasing Joe McCarthy and the Silver Jews, premature perfection.

If the reader doesn’t care for Ted Leo or Aimee Mann to be compared to the Gin Blossoms, I understand. I always get Tempe’s temporary hitmakers confused with the Friends fountain band myself. I’m not saying that The Both sound like the Gin Blossoms (though I don’t think anyone can deny that the dead fella in the latter band could write a tune). I’m just saying that it’s been a while since mature (in the good way), not schlocky, not novelty, not Weezer guitar pop has been attempted, let alone attempted successfully enough to make the Billboard Charts. The Both’s s/t hit #59 with a bullet, robbed of the coveted #58 slot by The Legend of Johnny Cash (apparently, in 2014, there were enough people on Earth who still didn’t own a copy of “Hurt” to deny our heroes their flowers).

(If the whole Gin Blossoms thing bums you out, we can push the whole thing back to Matthew Sweet and/or Julianna Hatfield’s early ‘90s work. But *cough* I’m gonna need to fudge some numbers.)

Ted Leo and Aimee Mann's fan base is an audience which reliably makes up 100% of the informed electorate in every election for city comptroller is nothing to be ashamed of. Being smart and/or amusing are not negatives unto themselves. I’m concern trolling only because sometimes, when a band is considered to be “reasonable” or, worse, “literary,” the resentment rolls in. Critics may initially enjoy an artist that they see themselves in, then eventually recall that they don’t actually like themselves, so why are they heaping all this praise on a band which reminds them of themselves, but with better shoes, and whose audience is the critic’s mirror image, but with more successful podcasts? Then adoration turns into faint, then fainter, praise. Before finally resulting in the band being denounced as the purview of condescending ex-boyfriends or as exemplars of a racism-coded tweeness which the critic had long suspected, despite the 5 out of 5 cheezburgers they’d assigned the artist’s first few albums. The self-loathing inducement to give wedgies to the differently smalls is rarely contained to just an artist’s fanbase. So it helps to stock up on some dummies and/or assholes, even as ringers, to balance out one’s crowd. This can be accomplished easily enough. Either by getting super famous, making alcoholism as part of one’s aesthetic brand (ala the Replacements and Hold Steady), “just asking questions” about vaccines, or simply being really into WW2 collectibles. The last one is the easiest, with the greatest amount of plausible deniability. Which is why I advocate for a preemptive solution that I call a “Motörheadiean Threshold,” which guesstimates the ideal number of idiots one’s band should have in its audience. Ideally enough so that nobody can accuse your music of being “literary” (i.e.harmless or bourgeois). Not so many that you become Pantera.

It can be argued that both Ted Leo and Aimee Mann are aware of the Rule of Lemmy and have, consciously or not, taken steps to address it. Not for nothing has Mann’s music been covered by Gang Green. And, for Mr. Leo’s part, as his younger mod fans reach that inevitable crossroads where an aging punk must decide whether to go full Paul Weller or drift into rockabilly and hope for the best, his fan base may diversify into dumber/more awful territories. Besides the resultant music (which will undoubtedly continue to be excellent), Leo’s further explorations of his Irish heritage might also bring in, besides some bonny lasses and a number of fae, enough Celtics fans to up the Too-Ra-Loo-Ra-Loo-Ral factor of his audience by an entire dropkick. And if confusion between Chisel and The Chisel continues, who knows? If the numbers hold, the crowd for the Both reunion shows could potentially be two thirds Portlandia and one third Green Room. Problem solved!

All this is theoretical as there's been no announcements, or even rumors, of the Both getting back together. Which sucks. Because the Both are so fab, so underappreciated for the magnificence that they were/are, that—even if their audience was nothing but literal angels who phone-banked for Bernie and were as winsomely witty as a young Emo Phillips, with nary a sketchy battle jacket in sight—I’d still be stoked beyond measure.

In that hope, a few months late for its 10 year anniversary, let’s get into the album. Yes, I’ll be continuing the Lemmy comparisons. But, more than that, I’ll be arguing that the Both, regardless of their audience or circle of friends, are perfectly unreasonable. Not villains themselves, but a duo whose songs have a mean streak, with the duo’s affable relatability proving to be a facade when one digs deeper. I’m arguing that the Both—in their unerring command of the language—are as innately monstrous as pop music demands. The Both, I’m saying, are misunderstood. Possibly as a strategic choice, with the unrelentingly lovely intertwining of their voices and the likably naughty cartoonishness of their “Ed Leo” mascot serving as a bit of sly misdirection to distract from the hard edge of the songs, where for every romantic exaltation is shaded/outnumbered by a clear-eyed view of human nature which borders on emotional realpolitik I’m saying that the Both are more Lemmy-esque than they themselves know. Like the Motörhead song “I’m So Bad (Baby, I Don’t Care)” says, the Both are bad (in the positive sense), baby, and there are limits to their sympathy. (And I’m not just saying that as wordplay because Mann once, in song, strongly implied that Al Jourgnesen was a fucking crybaby.)

At first glance, comparing either Mann or Leo to the singer of Motörhead is incredibly stupid. Maybe on second glance as well, considering that The Both begins with “The Gambler,” a song that, from its opening snare roll, can be interpreted as a line by line rebuttal to “Ace of Spades.” If not to the Motörhead song itself, then to a friend or lover (or, possibly, sibling) who’s taken being born to lose as far as their interlocutor is willing to go, regardless of the (friendly/romantic/familial) bond the two once shared. Even if some sort of methamphetamine is perhaps a commonality between the gamblers depicted in “Ace of Spades” and “The Gambler,” the subject of the Both song is presumably inspired to act out their Lemmite tendencies by something a few degrees separate from the source material; be it their own childhood/young adult trauma, one of the many Peter Pan syndromes previously celebrated within the counterculture, or just the discography of the Afghan Whigs. Whatever the cause of the subject’s fecklessness, when they trot out the hard-to-argue-with refrain of “I know… but I don’t want to live forever,” Ted and Aimee are a unified (if exhausted) front. The duo sing, “The well's dry, I'm out of empathy / This shouldn't end with both of us dead.” It’s clear that, if the second line is an intervention which has been tried before, the first line is new. Whether the well being dry is meant as tough love or as a final goodbye is left unresolved. Maybe it’s all been tried before, and maybe that’s how the gambler and gamblee like it. After all, if the listener is wondering what could have gotten characters of such disparate worldviews together in the first place, the intermittent shoot-out-the-lights growl of the song’s guitar line makes clear that the singer(s) have more in common with the joker at their door than they’d maybe care to admit.

Two and three songs later, in the dual tuffs of “No Sir” and “Volunteers of America,” Aimee Mann’s basslines—the former a waltzing bit of approaching thunder and the latter a fuzzed, dragonauted lathe against the song’s high harmonies and higher guitar chimes—make clear that all parties involved are capable of inspiring a reasonable person to change the locks. Of course, on “Volunteers of America,” the Motörhead comparison—which, fine, is already tenuous—is a bit undermined by the lines “With your thousand-yard stare / And your caretaker's hair / I guess we're not sleeping again / You're up there online, building your shrine / A go-to solution that then / Come tomorrow, you'll tear down again,” easily the most Steely Daniel lyrics that Theodore Leo has ever sung. Conversely, assumptions and expectations being undermined is a recurring lyrical theme of the album. Feel free to go into the songs expecting easily parsed worldviews regarding heartache and left-leaning politics. The Both, a roller skater, are gonna show you later.

A somewhat facile view of The Both is that it’s an album about two songwriters who treasure the craft of three minute (four minutes and forty one seconds, tops) songwriting, friendship, and the bands Loud Family and Thin Lizzy. In discussions about the album, there’s usually a focus on how the two songwriters balance each other out. In this narrative, even when noting that the two initially met through Scott Miller (the country's premier pop scientist in the years before the term came to mean someone who nitpicks about Star Wars), Mann is cast as the pop classicist who has Hal Wilner on ouija board speed dial and sleeps with a copy of the Virgin Suicides soundtrack under her pillow, with Leo playing the role of the spikey-jacket veteran of Revolution Summer, unpracticed but as feisty as the leprechaun from that Jennifer Aniston movie. Basically a Poguesmalian* urchin, one part Nel and one part Nell, who Mann teaches how to speak Brill and, through the power of pop, transforms a tramp into a Supertramp, to the amazement of everyone in Laurel Canyon.

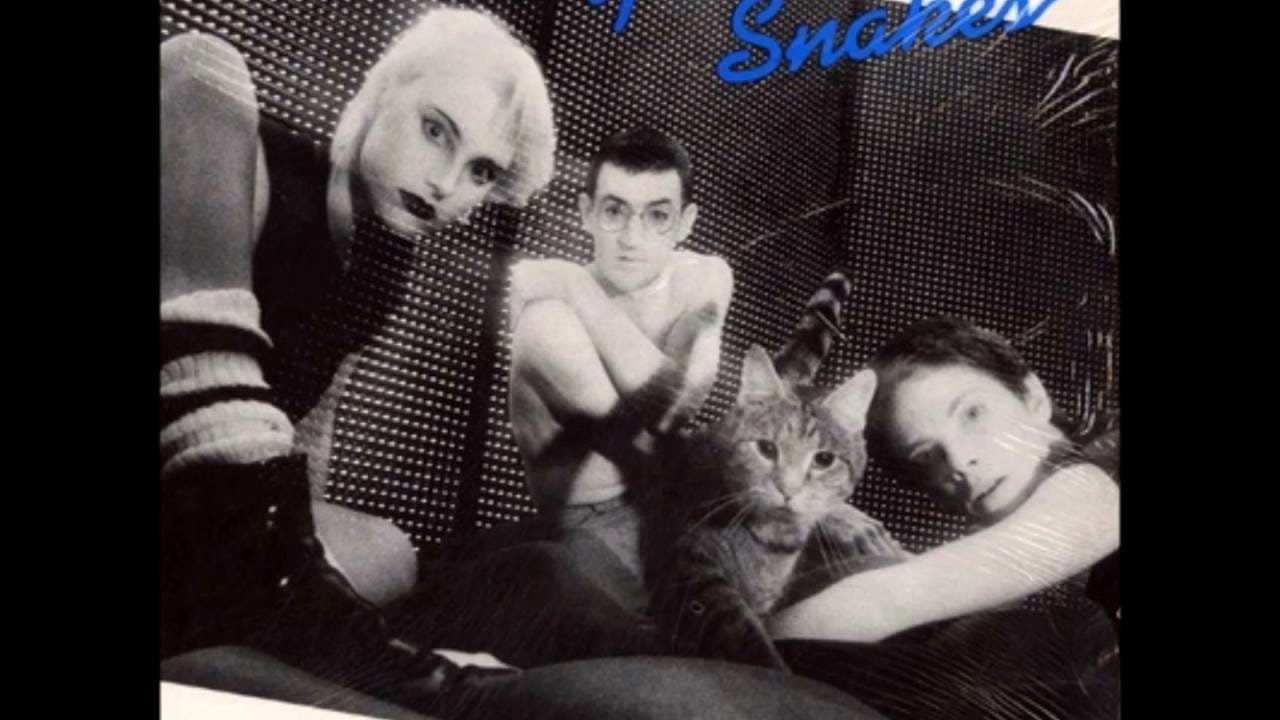

I may be exaggerating. But only a little. Even without the hyperbole, the truth is a bit more nuanced. Both artists come from punk/punk adjacent backgrounds, with Mann having no waved in Young Snakes before she new waved in ‘Til Tuesday—a band which, regardless whether or not the label would have preferred they sound like Berlin 2 Electric Boogaloo, was often more interested in sounding like a slightly funkier Japan (with Mann herself playing like she was a fretted-up Mick Karn doing side work in Beefeater). Not to mention that, lest one doubt her FSU credentials, Mann is—to this day—the only woman that half the bands on TAANG! have ever met. And both artists have pop rock credentials to spare. Historical pedants might take issue, citing Empire’s influence and how Fugazi was so much fun (and then forcing you to stare for days, Ludovico style, at a picture of Guy P. in that goddamn basketball net), but Leo’s hard mod outfit, Chisel (no “the”), was the first rock and roll band that D.C. hardcore types trusted. Before Chisel (formed in Indiana but claimed by D.C. on account of drummer John Dugan having been in Indian Summer and Leo looking like a bit like a handsome freshman senator), if you went to our nation’s capital and asked for even a vaguely rock album they’d look you up and down like you were wearing a wire and say, “are you in Junkyard? You have to tell me if you are,” before finally rolling their eyes and giving you a copy of Dag Nasty’s Field Day and scurrying away and hiding, like sticky pawed raccoons, underneath the front porch of Dischord House. Point being; both artists had great hair back when having great hair could still get your ass kicked and both artists loved pop rock—be it Steely Dan or Dexy’s Midnight Runners—back when loving pop rock was considered counterrevolutionary by a majority of the great-hair-having set.

Not all of the above aspects** come into play with The Both. I’m firmly on record as being ideologically opposed to the use of “punk energy” as an inherently positive phrase to be applied whenever a reviewer likes something with a bit of pep. So I’ll spare us all that embarrassment while discussing a project which has no sonic relationship to the genre. (Though, fallen as our society is, I know I’ll have to say, again, that something not being punk is not an inherent negative. PUNK IS NOT THE GODHEAD MERIT FROM WHICH ALL GOOD THINGS DERIVE. Please, I beg of you, grow up.) What the Both does is revel in the pop end of the guitar rock spectrum. Overtly with a cover of Thin Lizzy’s “Honesty Is No Excuse,” pretty overtly with the recurring use of the Chamberlin M1 and Mellotron 4000D (in case you were wondering if the Virgin Suicides soundtrack would get another mention), and somewhat less overtly with half the songs spiritually akin—in tunefulness and barely sublimated rage—to Steely Dan’s “Dirty Work.” As for all that punk energy you’ve heard so much about? Yes, dammit, it’s there. And it’s supplied by two rambunctious souls with a shared appreciation for (I assume) Squeezing Out The Sparks era Graham Parker and all the more driving good works of Jeff Lynne (anyone who has a problem with that association can take it up with J Church).

If there’s any noticeable change in Leo’s particular songwriting, it’s in the singer’s phrasing. With the Pharmacists, Leo has never been shy about bullying the shit out of a syllable. He does so (with “Where Have All The Rude Boys Gone” being a nice illustration) by either cramming a bunch of them into a single locker, or by taking a single syllable and throwing it onto the rack till it’s stretched long enough to reach the bridge. With The Both, no syllables have been harmed. Normally, if Ted Leo has something complex he wants to express, he’s going to make it fit. Sometimes to the point where his quick intakes of breath in between outbursts is as much a lyric as what’s sung. Conversely, with The Both, Leo cuts his verbiage in half. His work with Mann is so contained, with nary a syllable spilling over, that you’d almost think he didn’t grow up listening to the Subhumans (UK).

As for the drawing out of syllables, the absence is less pronounced. Possibly because Leo and Mann’s voices are so well suited for each other that—when the two combine to push out a word like “regret” or pull back together on an entire line like “So, the bones we buried in the yard last season / Cheerful, they remain”—any additional i-yi-yi-yi-yis or ow-owo-owo-wos are unnecessary. I don’t, however, know how much of this latter restraint is Mann’s influence. She’s an avowed art-rock fan after all, and has far too much good taste to have an ideological issue with Leo’s complexifying of a phrase in the Pharmacists. And she has her own wily way around a phrase, as even anyone who is definitely planning on getting around to watch Magnolia one of these days can tell you. Further, if she did suggest any toning down of Leo’s patented way of ending a phrase with a Sandy Denny-esque call to prayer, it’s probably only because, with her Steve Vai collaboration in 2012, she’d already indulged that tendency towards North Star Grassman and the Ravens proggishness which we all feel from time to time. I suppose what I’m describing in both artists is what is commonly referred to as “singing.” But I’m not making up that Mann and Leo adjust/subsume their own idiosyncratic styles for the Both project (kind of like how the goddamn band name is making me spell out the individual artists’ names as to avoid nave multiple “both”s in every other sentence of this essay).

This is not to say that what either singer does together is better (or worse) than what they do when left to their own devices. I saw Ted Leo + Pharmacists play Shake The Sheets in its entirety the other night, and if any of those songs were complicated by tics, nobody told the sold out Warsaw crowd singing along to nearly every word. And as Leo is one of the best lyricists going, I’m never looking for less words from him***. The same applies to Mann. As cliche (and arguably gendered) as the short story writer comparisons may be, there are few songwriters who do as much to build a scene (and document its being torn down), with such an economy of language. And I’d happily purchase a triple album of her writing songs about nothing but cats. Even as she enters her Dory Previn Era on 2023’s terrific Queen of the Summer Hotel, Mann’s scalpel work continues to be as much devoted to self-editing as it is to cutting the motherfuckers in and out of her mind. On The Both, it’s a genuine kick listening to Leo adapting to and adopting the comparative lyrical austerity of his songwriting partner. With neither singer capable of hiding their weird intelligence—but with both of them keeping each other’s rhyme scheme honest—what the pair end up implying is a lot.

So, on a song like “Pay For It,” with it safely assumed that the song is not about either of the singers’ respective real-life partners, the song can just be about the vicious, nagging undercurrents that come with loving someone so much that you almost know them (and they you),and with that near knowledge comes the suspicion of what any lover is capable of, even/especially on the smallest scale. The listener may be lured into a false sense of familiarity by the prosaics bread, colds, and package stores, making the causticity of the chorus, which is just a repeated refrain of “you’re gonna make me pay for it / you’re gonna make me wait for it / you’re gonna make me pay for it (now)” that much more bleak in its repetition.

The lyrics on The Both are neither oblique nor explicitly diaristic. I don’t know what most of the songs are “about” per se. With pop rock, this can go either way. On, say, Screeching Weasel’s My Brain Hurts, everything being spelled out is a virtue. On Dylan’s Desire, the weakest songs are the ones where the veil falls and the listener has to wonder why this weirdo is sanctifying some jerk-off mafioso. On Mann and Leo’s album, the prioritizing of universal joys and dreads (still with a degree of the specificity which the artists make such uncanny use of in their individual work) is a pleasure unto itself. It can be momentarily distracting when, on a song like “The Inevitable Shove,” a listener such as myself—who loves the song near unconditionally but who’s been somewhat brainwashed into taking lyrics as literal expressions of what the singer had for lunch that day—can’t help but wonder if we’re expected to believe that there are people on earth who are looking to dump either Ted Leo or Aimee Mann. And when Mann and Leo try to claim that “Milwaukee” is a love letter to the city and the human spirit, the human spirit—being pretty sure that cities can’t get pregnant, not even in Joe Biden’s America—might be inclined to buck at this seemingly woo woo obfuscation. Again, momentarily.

Because then one adapts and realizes that in the The Both cosmology, songs can be about anything! Even stuff unrelated to specific trauma! The duo isn’t here to be “relatable” in the way that we’ve all been trained to expect in the last few decades, ever since Kurt Cobain made meaning it the law of the land. Instead the Both is working in the tradition of Carol King, Dean Wareham (sometimes), Smokey Robinson, and New Pornographers (i.e. the songwriting tradition of saying True Things—as shifting in their meaning as late night pillow talk, largely urbane, but applicable to one’s life regardless of one’s circumstances—for Now People. And also maybe showing off how easy they make a near impossible thing seem). These songs are more concerned with the tapping of psyches of romantics and neurotics than they are in making Netflix documentaries. Once that’s understood, the album takes over on its own terms.

In this light, it becomes clear that the album closer, the aforementioned “The Inevitable Shove,” is not about being dumped by a lover. It’s about the protagonist’s own fear and insecurity; manifesting as certainty. As Leo and Mann are both two of the more successful performers from their respective milieus—and assuming that the song is neither a veiled confession, told empathetically from the perspective of some aggrieved ex-‘Til Tuesday or Animal Crackers members, or about losing bandmates to the 8G Band—it can again be granted that the singers are doing a fiction. But that hardly matters, as jealousy, in any context, does its own work. Sometimes our more successful friends/lovers/bandmates do tend to disappear. Only to reappear—their belt buckles shinier and their cheekbones somehow a bit sharper—a few rungs higher up the social ladder. But the inevitable kiss-off is just as often about the abandoned party feeling, even before they got ditched, like their being loved is impossible, and then their projection of that feeling making any “inevitability” a self-fulfilling prophecy.

(It should be noted that the Both aren't helpless to inject a bit of venom in every song. "Milwaukee" might not be Chamber of Commerce pamphlet the duo claims it to be, but it's still unapologetically big hearted about friendship and, yes, the human spirit. And "Bedtime Stories," the Both's tribute to Scott Miller, is both sonic homage to their friend and emotionally uncomplicated in how it expresses fondness for the man and his art, and the grief the two continue to share in the wake of Miller's death. The song's end round robin refrain of "So come on and trace me that arc / So we won't have to wait in the dark" may touch on a similar bleakness as some of the more caustic lines found elsewhere on the album but, in this case, the pattern is reversed. Mann and Leo are acknowledging the external sorrow, which—death being the bad penny it is—they can't do much about, and undercutting that (both lyrically and in the—I think—mellotron which provides a beaconing hallway of owl hoots at the end of Leo's guitar solo and under every chorus).

As it has entered its period of ten-year hagiography, people will try to paint 2014 as some phenomenal year for music. It was not terrible as, since the industry imploded, there haven’t been any terrible years for music. As far as “great” albums go, in terms of things that was both reasonably popular at the time and holds up as art now, it was pretty much Vince Staples, Iceage, Azealia Banks, Yob, Swans, Against Me!, Tinariwen, and I guess FKA Twigs or Perfume Genius (both artists too far outside of my wheelhouse to judge but included because, if you tell me they’re brilliant, I believe you… feel free to switch them out for whatever pop and/or electronic artist you prefer). Plenty of good, solid stuff came out, even with Perfect Pussy and White Lung coming in to illustrate horseshoe theory before the term came into vogue and simultaneously bring the year’s grade curve down to “sure, why not.” And, as with every year, there were dozens, if not hundreds, of wonderful albums that, for whatever reason, didn’t make many of the lists. There’s always going to be sublimely boffo bands like Noura Mint Seymali and Ibibio Sound Machine, who the universe creates so that the credulous, pot-addled assholes who prefer, like, the fucking War on Drugs or FUCKING SUN KIL MOON, have something tangible to repent when they meet their mustache maker. In that vein, we can thank Rolling Stone for naming U2’s album, Songs of Innocence (AKA The Forgettable Fire), as their album of the year. Listmakers didn’t know shit in 2014, so they’re free to not know shit today. Hence the fact that the 10 Year Anniversary ticker tape parade for The Both’s s/t album seems to be pending, presumably so Eric Adams can close a few more libraries and use the money to build a bigger Broadway. Or, as my grandmother told my dad in 1943, when he asked her if he could have some ice cream, “when the war is over, dear.”

I don’t have any expectations of any massive reappraisal of The Both. Nor is one necessary. The band was successful, the album well received, and its two members are thriving. On the other hand, they should have been even more successful. And it’s not like the protagonists of The Both songs are entirely averse to pettiness. So hopefully the band will forgive me my need to carry a righteous and trifling torch on their behalf. Still, I know in my heart that it’s contrary to the Both’s wry joie de vivre to harp on canon. They’re unconcerned, to the point where it’s arguable that whatever wounds I may feel have been visited upon this album were self-inflicted at the band’s inception. The first song the two wrote together was “You Can’t Help Me Now.” In interviews, Leo talks about how wounding, but eventually fruitful, Mann’s initial critique was. I like to think that the first draft sounded like New Model Army. The end result—with its half-martial, half-loping beat and its purring guitar—is as off-kilter anthemic as anything either has done (or NMA’s “51st State” for that matter). But the song’s rousing chorus is lyrically unpitying, both inwardly and outwardly; the first of a thousand of the pair’s undercuttings. Of course, if songwriters are somehow able to communicate even a snatch of the confusion and contradiction which occurs behind every other eye blink, in every millisecond of human interaction, and they can manage to capture those synaptic bursts in a three or four minute pop song, they should do so. That said, “You Can’t Help Me Now” begins with a startlingly apt first line for a band that's persistence in ‘70s-infused loveliness is matched only by their refusal to compromise in their depictions of ambivalence. The song starts with a few moments of pastoral guitar, joined by a dowsing bassline and followed by a feathered rush of snare, then Aimee Mann sings ”with “Any time you establish a world of your own, you get thrown.” So it’s not like Leo & Mann didn't know what they were getting themselves into.

I probably should have discussed the Both’s relationship to the alternative comedy scene. But I don’t know anything about that world. I understand it’s allure to the fair-haired duo but, raised Jewish, there’s never been anything alternative comedy could tell me that I didn’t already know****. Also, I forgot to do much with my Motörhead argument. Fuck. So, uh, the Both are like Motörhead in that “Hummingbird” is kind of like “Greedy Bastards,” Motörhead’s Thin Lizzy cover is almost as good as the Both’s, and maybe the Both’s appearance don’t hold no class, but I love them like a reptile all the same.

The Both, scaly baby, I see you shine.

*yeah, I know, I know… but I wrote this before looking the myth up and I like the joke too much to change it just because Pygmalian was the sculptor and not the clay. This newsletter is free and so am I.

**Regular readers know that if I could find a way to suggest some kinship between Aimee Mann and Junkyard, I would. I even spent ten long minutes cross referencing ex members of the hard schlock outfit and Ministry. No dice. No one is more upset by this than me.

***fwiw, Leo ably split the difference between all the various styles—taking in the restraint of the Both, nodding to the psychedelic melancholy of some of Mann’s solo work, and in turn writing some of the most free, paradoxically direct, and (especially in the case of “William Weld in the 21st Century,” “Lonsdale Avenue,” and the two “Moon” songs which bookend the album) straight up best songs of his career thus far—on The Hanged Man, his subtle, crushing solo album from 2017.

****I do enjoy the roll call scene in Wet Hot American Summer and Paul F. Tompkins doing Andrew Lloyd Webber on Comedy Bang Bang. Otherwise, I’ll stick to Spaceballs.

THANKS FOR READING. Please share/subscribe if you like. Please subscribe to CREEM. Please check out these two covers (Sheer Terror & New Order, natch) that Zohra and I did (and Zohra's album too). Please buy all the albums by Aimee Mann and Ted Leo.

Oh yeah I wrote Leo's bio and I think I did a swell job. I'm available for hire in that regard. Rates: $1000 for major label band, $800 for "indie" label bands, $300-$500 for indie label bands (depending on how convincingly you/your team can claim poverty), and negotiable for everyone else (but, if you're destitute, please don't make me choose the number... just tell me your budget and I'll tell you if I can do it).