Cartoon Violence

Welcome to my newsletter! This first one is WAY too long. I know. I just haven’t had a chance to write for a while so I went bananas. Feel free to skim. It doesn’t build to any “and that’s how The Crumbsuckers taught me to forgive myself” type shit. I promise all future missives will be shorter. But, free of editors or need for clicks, they will all still be maddeningly obscure (and forever devoid of any advice you can use). Also, I do have a paid subscription option. But do NOT feel feel pressured to use it. All my content will be free for now and even if you do subscribe, feel free to cancel if you just wanted to send me a few bucks. I will not be offended.

Thanks to Gary Suarez helping me set this up and to Zohra Atash for encouraging me (always). Also thanks to Fred Pessaro for making the HXCXHXC logo for me. He has a new non-profit that makes masks for any of you that need one. http://masksforthemasses.org/ And thank you! Here we gooooo…

The current working theory over here is that the caring about the music genre and lifestyle known as “hardcore” (short, in this case, for “hardcore punk”) is, in the masked antihero spring of 2020, a lot like caring about the Marvel Comic Universe. Using the “MCU” as a catchall term for all superhero movies/comics/intellectual properties. If DC comics wants to be the signifier, much as I prefer its actual mythology and canon, it can remember primary colors and teach its scriptwriters how to tell a joke. Anyway. To love hardcore in any informed way requires the same nostalgic energy and trainspotter’s knowledge of obscure characters that is required to sit through an entire Avengers movie without checking one’s phone or partaking in amphetamine salts by the shakerfull. This is hardly a novel observation. But if I was solely interested in the more subtle truths, I wouldn’t have a wall full of records of people yelling at me. It’s always clobberin’ time somewhere.

The first time I heard Born Against, I was fifteen. I’d given up on superhero comics a year or two before, at the start of the medium’s decades long descent into “gritty and realistic” confusing tedium. I was exhausted by the muted colors, carnage, and the joyless codenames and shrinking ankles. In exchange, I’d discovered The Clash, critic validated hardcore punk rock (Bad Brains, Germs, etc), and shoplifted pornography. An older kid noticed I wouldn’t stop lurking around the skateboarders and punkers so he figured I might as well start knowing what I was talking about. He gave me a mixtape with Crimpshrine, Jawbreaker, Youth of Today, Green Day (!), FUEL… and the band with a name tailor made for a certain type of adolescent: Born Against.

Sidenote: I may have already had a tape or two of Boston hardcore bands. I am from Massachusetts after all. But I still maintain that the only good band to come out of Boston, with the rhetorical alley-oop of considering Aimee Mann from Virginia, is Gang Green. SS Decontrol is for Negative Approach fans who respect the troops. Boston sucks and I don’t wanna talk about it. Don’t @ me unless you’re literally Tip O’Neil’s ghost.

Now you know two things about me that make my views on hardcore suspect (three if you count the above admittedly insane paragraph). You know that I am not currently a kid, the only marginalized group that all of hardcore’s various- right or left or nihilistic- doctrines can agree matters. And you know that I “wasn’t there,” in Los Angeles or on the Lower East Side in the 1980s, or even ordering 7”s from the ink stained pages of Maximum Rock n Roll. Hardcore is ostensibly for everyone but, regardless the scene or region, anyone who “wasn’t there” at the region or time in question is doomed to lose any argument, about anything, to someone who was. It doesn’t matter how many books you’ve read or albums you own or bands you’ve played in or seen. Even if you’re arguing with the most thick-headed amnesiac scene second-stringer, who on their best day was 25 Ta Life’s roadie for one show only, who is trying to tell you something objectively insane like “Murphy’s Law was wearing tracksuits before Mark from Supertouch.” As soon as they say “I was there,” hardcore rules dictate that they have won the battle and you are a suburban poseur. Considering that the lifestyle is dependent on the type for its commercial survival, being called a suburban poseur may not seem like the worst insult. You can go ahead and think that until it’s applied to you.

Despite these blows to my credibility, and the not having “been there” an original sin that there’s no coming back from, I am still both a person deeply committed to hardcore and a person deeply committed to being a person deeply committed to hardcore.

It says something about the transformative mythology of hardcore punk rock music that, when I first heard them, I assumed the members of Born Against must be extremely scary. Even for a wise and jaded fifteen-year old who religiously bought every Dischord release (or maybe because of that) “Mount The Pavement,” the first song of 1991’s Nine Patriotic Hymns For Children certainly didn’t sound like music made by nice or smart people. It sounded deranged and alien. (Like all the critics promised Sonic Youth was going to sound like, leading to my crushing disappointment when I paid good money for Daydream Nation only to discover that they just sounded like an out-of-tune and bored Neil Young cover band. A judgement that has softened over the years… but only slightly.) Born Against’s guitars sounded like a lab experiment had gone horribly wrong and given birth to a saw-blade-for-hands half-transistor radio robot maniac. Only by throwing all the hi-hats in the studio at it could Born Against hope to survive the rest of the song. The singer Sam McPheeters sounded like, maybe because of the M.A.R.K. 13 style robo-guitar-monster in the studio, he’d see us all in hell before he conceded any human language’s capacity to convey his rage and terror. Enunciation didn’t seem too high on his list of concerns either but, what with the robot carnage and flying cymbals, that was understandable.

I don’t want to get bogged down in the minutia of my teenage music discovery. Presumably you know or are other forty-somethings. Nirvana happened. Things on the charts got weird and then less weird. Some skateboarders got into Rollins Band or Pearl Jam and joined the marines. Everybody met their first riot grrrl and that was very exciting, though end results varied. Romantic teen comedies were briefly palatable, even delightful. Others made other choices. Heroin. Robitussin. Ska. Who could possibly care.

Not hardcore, that’s not who.

Hardcore, while fond of rap music and occasionally distracted by the siren call of Sassy Magazine and cheap suits, cares only for hardcore. Hardcore is site-specific art where hardcore is the site. (One could argue that the idea of “art” is antithetical to hardcore, but nobody can pretend that hardcore doesn’t love “sites.” Though in hardcore’s puppy dreams, the regional initials that balance out the “H” and “C” on the signifying “X” are just another “H” and “C”. ) Hardcore is a parallel universe where, whether the music hails from Japan or Brazil or Orange County, Reagan is always president and, like The Watchmen, ordinary people dress up in only slightly altered street clothes and fight crime or what they consider crime or each other. And like the Watchmen comic, it can be taken as either an obsessive consideration of the medium or taken at face value; team players and misanthropes alike righteously kickflipping their cares away under an empty, occasionally Krishna inhabited, sky. How you inhabit hardcore itself is up to you. Kind of depends on how you feel about varsity lettering.

Thinking Born Against were suitably hella scary, I didn’t know that they were any different from any of the other scary sounds coming out of New York City. This was my only relevant point of comparison as, by 1991, people I knew who liked Black Flag liked REM and The Dead Milkmen as well. Maybe what all those west coast urban cowboys did was secret at some point but by then it all scanned as party music and wasn’t it funny that Belinda Carlisle used to be one of them? Cali hardcore was practically classic rock except with funnier/more “shocking” song titles to put on mix tapes. Obviously in retrospect it was a misconception on my part but It’s hard to consider a band scary when they’re called the “Circle Jerks” and everyone in drama club knows their songs from the Repo Man soundtrack. If you’re reading this and you lived and died in LA in 1983, no disrespect intended.

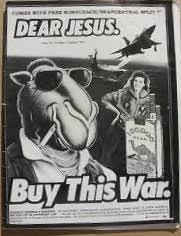

Reading Sam McPheeters’ “Dear Jesus” zine (which I got on a trip to NYC with my dad and his boyfriend) was the earliest indication I had that the scene Born Against inhabited was decidedly different than that of Youth of Today and Gorilla Biscuits. I read McPheeters’ mockery of Krishna-core well before I actually heard Shelter or 108. I wasn’t so naive to think that all interpersonal conflict would come to an end if and when I graduated high school. After all, I pored over Minor Threat lyrics so I knew betrayal was a major component of this hardcore lifestyle but I hadn’t been betrayed in any real way. (also in retrospect, it would appear that much of the letting down of friends in my life was done by me rather than to me. But that’s for a later essay that I’m never going to write.) I read the columnists in MRR so I knew that Ben Weasel thought Fugazi was boring but even then I had an inkling that there’s a fine line between personality and schtick. But I grew up in a small enough town that the only enemies I could feel on a visceral level were jocks and our (five) cops. Of course later, once I started playing music “professionally,” I picked up quick that a visceral hatred of one’s peers is one of the singular pleasures of being an artist. But that’s not something they teach you in post-punk school.

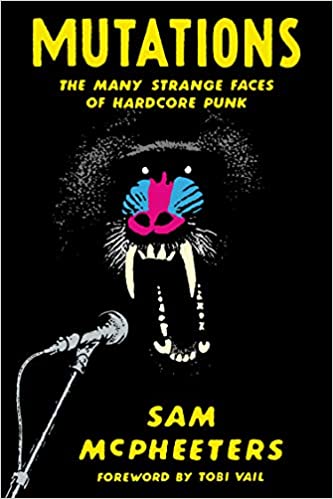

The inter-scene warfare is consistently alluded to and sometimes discussed at length in McPheeters’ new book of essays “Mutations: The Many Strange Faces Of Hardcore Punk.” In the context of autobiography, profiles, and criticism, McPheeters approaches these seemingly endless conflicts, some resolved with age and some not, with a ruefulness that occasionally veers into apology but usually stays in the lane of bemused self loathing. This tone of self recrimination is consistent throughout the book. If it occasionally grates it’s only because it’s annoying to read the man discount his own considerable work (he can write it off but Born Against really was a wonder and his fiction is far better than a lead singer should be capable of), and also because it occasionally feels like a device- a way of eliding the fact that the post-teen McPheeters who thought a number of his peers were dumber than hell mouth-breathers still inhabits a small portion of middle-aged McPheeters’ heart.

I might be projecting a bit on the second part.

Still, I tore through the book, dread growing that there was never going to be an addressing of the “Great Born Against Versus Sick Of It All Radio Brawl.” And it was with joy akin to those cheering in the theatre at Captain America being able to lift Thor’s hammer in Avengers 3: Trillions Dead Ain’t Nothing But a Number that I came to page 167, the chapter where McPheeters gives hardcore’s greatest/only offline debate its proper postmortem.

For those unfamiliar, SOIA is a New York hardcore punk band (more street punk these days) whose individual members have diverse views (ranging from conspiracy minded libertarian to Regular Joe liberal) but that collectively have the politics of a particularly ornery Daily News columnist. They hate Robert Moses and love the working class that they came from, but there’s a degree of machismo mixed with raw populism built in and punk bands signing to major labels has never been high on their list of concerns. Also, they have a song called “Clobberin’ Time.” Born Against hated machismo, sell outs, and, while being pro working class on principle, people in general. They were an archetypal ABC No Rio band; the antithesis of the athletic thuggery of CBGBs matinee hardcore. In spite the feral brutish rage of their music, Born Against were the caustically brainy kind of band that, even though none of them wore glasses, also kinda did? Anyway, in 1991, on air in the studio of WNYU, words were exchanged and, depending on what version you subscribe to, either a chair was thrown against the wall or a Born Againster was straight up clocked by a representative of In-Effect Records (SOIA’s label at the time). The tape of the interview, before the internet made it accessible to all, was passed around for years, like a missing volume of the Kabbalah.

My cheeks are legit turning red just typing all this out. Before typing it out, I tried to explain it to Zohra and my cheeks flushed with embarrassment then too. Like trying to explain that Captain America actually first lifted Thor’s hammer in issue 390 (Vol.1) of the comic book “Thor.” Well, technically it wasn’t Captain America because Steve Rogers was just going by “The Captain.” In no universe is any of this useful knowledge. It takes neither the perspective of pandemic nor endless war to make a college radio fight between small-difference punkers seem wildly inane in the telling. Members of both bands themselves are bemused at the historical weight attached to what was detritus even at the time. It’s like being caught watching missionary position porn. With all the effort involved, the stakes ought to be higher.

That’s one of the qualities shared by comic book and hardcore music fandom though. Part of the pleasure is in the knowing, the referencing. Actually reading the ‘70s run of Guardians of the Galaxy is torturous. Knowing it exists is enough. Of course there are pedants in both arenas, those who claim that the most obscure works are actually better than the canon. I’m often that pedant! While gatekeeping is a tiresome and inarguable evil, pedantry is one of the supreme satisfaction of loving these arts. To the point where “quality” (whatever that means) of a work is equal to its just existing, before, after, and in the context of other works that the fan can love or hate, argue about, or, joy of joys, just file away, displacing less essential memories like anniversaries or friendly acquaintances' names. In my heart I agree with Sam McPheeters’ brave truth telling in saying the Cro-Mags first album is superior to the band’s early demos. But it’s the minutiae that makes the universe.

(In this not-at-all-strained comic/hardcore analogy there are obviously works in both camps that merit regular re-visits. The Fantastic Four's first appearance of Galactus is Minor Threat’s first EP, the Sheer Terror discography is pre-crank Frank Miller’s two Daredevil runs, and, obviously, the Kree-Skrull War is Age of Quarrel.) (I hate to keep picking on DC Comics by omission. I do love so much of it. But much of its ‘60s/’70s output is, like, Donovan in Don’t Look Back.) (OK fine. Ummm… Paintbox’s Trip Trance and Traveling LP is like Justice League Unlimited. Happy? Great!)

Even while agreeing with all parties involved that the WNYU SOIA/Born Against kerfuffle was silly, I still thrilled at the Mutations essay. Besides that fact that McPheeters’ is a sharp and entertaining writer, when reading about a minor event talked to death over the course of thirty years, just knowing more details satisfied the same urge that sent me to pore over issues of Who’s Who in the DC Universe and The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe as a child. Honestly, while I don’t want to affect book sales by offering up spoilers, I can’t wait till the bars reopen so I can find literally anyone with a garbage neck tattoo, interrupt their attempts at post-covid coitus, and talk their ear off about the chair throwing proclivities of former In-Effect staffers.

McPheeters has an expansive view of what constitutes hardcore punk. That or he plays loose with the genre’s many definitions to fit what essays he wanted to include under the umbrella of the “many strange faces of…” in the book’s subtitle. Or he uses “hardcore” as a less self mythologizing catchall for the “underground” lifestyle he’s lived. All are valid. Hardcore, while venerating their bands (or hating said bands to such a degree that it might as well be veneration), is so much more than the coastal tattooed love boys and their reverberations and clones. Meet Me In The Bathroom is a perfectly true representation of one facet of New York music at the time, but Lizzie Goodman is the first to admit that there could be an alternate version, with entirely different bands, that would be equally true. And hardcore is *cough* significantly more diverse than early-mid-aughts NYC indie rock. It would take a hundred different book length versions of Mutations, with a hundred different resultant essays, just to capture a few notes of all the speed and volume of hardcore’s variety.

For McPheeters’ cosmology, hardcore is all the freaks he won’t stop thinking about. Certain artists, even if not sounding like Madball, are intuitive. While disinclined to pit, the almost blinding combined punk cred (Slant 6, Bikini Kill) of the members of The Casual Dots would merit the band’s inclusion even if Wire wasn’t the musical and/or spiritual blueprint for all hardcore people who dress real slick and “12XU” wasn’t arguably the first hardcore song. It’s no diminishment of the music made by The Casual Dots or its individual members to say that the culture(s) they created- through art, politics, and inspirational style- brought as many souls to hardcore/punk salvation as the songs. And McPheeters’ ruminations on the art that came out of Fort Thunder makes sense when put in the context of the author’s post-Born Against spastically inclined art damage music. (I don’t have much to say about his 1993-2002 band, Men’s Recovery Project. By the time they were in full swing, my heart was equally but fully shared by goth and Sheer Terror. There just wasn’t room in my chest cavity for that many 7”s.) And if hardcore is a lifestyle above all else, there’s no reason not to have brief examinations of counter-pop practitioners like The Flying Lizards and The Gossip alongside (unintentional) doctrine setters like Die Kruezen and Discharge. Also, Mutations is McPheeters’ book. He can do as he pleases.

Over almost thirty essays spanning more than thirty years, Mutations gives full thrift to the expansive cast of character actors that make up that niches of hardcore that McPheeters’ rolled around in. Thankfully, there’s few marquee names. We’re spared the professional hardcore documentary talking head triumvirate of MacKaye, Rollins, and Grohl. Instead we get a bracing dialogue with professional bracing dialoguer, Aaron Cometbus, affectionate(ish) portraits of Thrones’ Joe Preston and MRR founder Tim Yohan and, in the book's highpoint, a heartbreaking profile of 26 from The Crucifucks.

McPheeters is a compelling writer, both honest and endlessly quotable. He’s also unremittingly ambivalent about the manic pass time he’s devoted much of his life to. But why? Setting aside such prosaics as lifelong friendships and art both sustaining and thrillingly transitory… All these characters! All these fabulous names! All these costumes! From the leather of d-beat bands to the frayed French New Wave preppy-isms of Washington DC/Portland bands to the Mad Max Football Hooligan streetwear of NYHC to even the regimented anti-glamor normcore of McPheeters’ bands, how can you not think of adventure and, yes, superheroes?!? Of course, the music is swell. Of course. You can find music anywhere though. But only hardcore punk, at least now that Parliament style funk and electro is less a going concern, offers up such a weird and wild array of codenamed and ridiculous characters. Hardcore may largely fetishize the idea of authenticity as a singular virtue but that’s a self delusion verging on a sham. It is not inauthentic to ritualize the jumping off of a stage into circling- clockwise or counter, depending- mass of costumed yahoos, rituals get the demons out, but nor is it any more authentic than attending church or any other strain of the theatre. Captain America is a real American and Bugs Bunny is genuinely wascally.

All these characters, their codenames and individual dramas, are as important as the art they made. Hardcore’s supposed aversion to shit talking, name dropping, and “drama” is laughable on it’s face, unless we actually just want song after song on the evils of wearing suede. Like superhero comic books, hardcore is averse to innovation in both the stories it tells and the how it tells them. It exists as a series of lizard brain callbacks, tropes, and templates. Who hurt whose feelings. Power. Responsibility. Tight pants vs. a panoply of pockets. How can we use Animal Man and make him feel new and old? How can we do the same with Deadguy? None of this is an insult. New is not an inherent virtue.

Whether cartoonishness is an inherent virtue is also up for debate. I both love the sound of tough guy hardcore and I have always attached a degree of toughness to hardcore I loved, whether it be the implied psychotics of Born Against, the lurch of Nausea, or the stabbing defiance of Bikini Kill. And, even having been beat up plenty and not enjoyed it once, I have always loved the danger of hardcore performances and I’ve always loved the danger involved in stories about the performers, even while cringing at the thought of actual people (or actual me) getting hurt. And that’s the riddle that all fans and participants, at least the ones who don’t truly enjoy inflicting pain, need to contend with. The stories of NYHC luminaries hunting down and smacking the shit out of every member of Integrity is funny (to me, even while I love the band. Maybe not to you). The teller is usually a natural raconteur and there’s a madcap looney tunes aspect to the telling. But the reality remains that the beatings were probably somewhat less madcap to the members of Integrity, their legs circling in the air before they fell to the canyon floor to await the rapidly descending ACME anvil. But also, even the musicians and fans who decry violence in all its forms are still drawn to this violent kind of music. Painful as it is for me to admit, there are other kinds of music. Freak folk is always hiring. But we don’t leave, not all the way. We complain about the jocks, the bullies, the bigotries and hierarchies. And when it all gets to be too much, maybe we’ll split off and put out a middling synth-pop album with questionable aesthetics or two, but some tendencies can’t be satisfied anywhere else. Conflict isn’t the frosting, it’s the cake. And apparently cake is yummy. Like Anthony Keidis, we enjoy our pleasure spiked with pain, but for cakes. After all, Fugazi made a lot of speeches... but the fan favorite will always be the one where Guy humiliates the ice cream eating motherfuckers.

McPheeters wrestles with this a bit in Mutations. He hates the mindless violence so built into his hobby of choice/fate but he doesn’t lecture against it. He tells of near riots at The Smell with both verve and a gleeful contempt while he doesn’t hide his preference for the thuggish heft of bands like Cro-Mags and SSD over the distinctly faintly praised capital “G” Goodness of the Washington DC Revolution Summer bands. While he strives for empathy for his lifetime’s worth of enemies there’s also the occasional whiff of an aging Free Speech Guy’s disdain for the serial weakness of others. It’s never explicit but it’s there. I say that without harshness. As I grow older, the lure of Free Speech Guyness beckons on the regular. I just, in practice, like McPheeters, prefer the company of politically correct weirdos. They’re kinder to me and have better taste in pop-punk.

McPheeters claims to at least partially hate hardcore, but I don’t believe him in the slightest. McPheeters can tear at his Spidey-Man underoos all he wants but the proof is in the pudding at the end of the book. Peter Parker wouldn’t have forty pages of footnotes on the topic if he thought web slinging was a waste of time. Thirty Five years after Watchmen, Alan Moore is still writing superhero books. So we all are with hardcore. It’s hard to break with mythology. In days this dumb, considering the god/master options; podcasts, disease, Tame Impala… who would want to? As far as hobbies go, a person can do worse than collecting comic books or thinking about hardcore punk way too much. Perhaps neither appropriate for an adult but it’s too late and too expensive to get into cars or guns. If I’m no longer a kid, and I’m only here for whatever is happening now as a middle aged witness, then I’m the weird dude standing in the back again, tired of the cynical death urge of mass culture but still wanting the colors and capes and ecstatically confusing backstories. As far as human conditions go, there’s a precedent for lurking at the edge of the pit. It’s nice to be part of the continuity.