Crisis On Swiftinite Earths: Notes On Tortured Poets Dept.

As far as subsisting in a simulated reality goes, there are worse matrices to toil under than this one built around the love and laughter of Taylor Swift. It’s maybe not so many laughs for those NPCs within the immediate orbit of our Main Character. Imagine a coterie of aspiring mega-celebs, names heavy with extraneous vowel sounds, grinning like the parents and townsfolk from the “It’s A Good Life” episode of the Twilight Zone, knowing that any stray wrongthink might result in being turned into a jack-in-the-box or, worse, having a song written about them. But for the rest of us, operating as though we had free will in the furthest reaches of the Swift extended universe, the life of a satellite can be a fulfilling one. We can “choose” to not even talk about Taylor Swift if we don’t want to. We can talk about other pop stars. We can talk about war and famine. We can live out our avatar lives, deluding ourselves that we actually care about stuff other than the northernmost star in our sky’s propensity for banging out the English, her online firing squads of deranged parasocial besties, and her flattening of interiority till it’s diffuse enough to be related to by anyone who’s ever had their heart hurt by a varsity liar with a funky fade. We can pretend other music—music coming from sects with improbable names like “Black Flag” or “The Beatles”—exists, that there sounds in the universe other than the wind, cars honking, and the songs of Taylor Swift which are transmitted directly into our skulls via esoteric numerology and the careful curation of Capital One’s ecclesiastical disc jockeys.

Sure, we can do that. I, however, don’t much go for denialism. I’ll take red pills, black pills, pink pills, whatever i can buy with GoodRx and wash down with a Coke Zero. Of course, knowing that all that one perceives is illusory isn’t the same as doing something about it. I suppose I could take arms against the simulacrum. Black trench coats don’t really flatter a classically urban-semitic physique, but I do have a black Crombie jacket I like to wear out when I’m entertaining self-delusions unrelated to dystopia. On the other hand, once you tear away the grand facade, you don’t have much choice but to hang out with other veil piercers exclusively. There are no magical sunglasses. You can’t go back and forth between gnosis and know-jack-shit-ness whenever you miss hanging with the boys. You’re stuck with your new steam-punk friends, talking your ear off about Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, at a Burning Man festival on the moon (the real one). The only consolation is that the sheer volume and ever increasing bpm of Grimes’ DJ set makes conversation nearly impossible.

So, putting a pin in the systems of control stuff, I’ll take the present reality as I currently perceive it. Which, in this case, means writing about the LP just released by Taylor A. Swift, our own mad and laughing god of West Reading, Pa. The middle initial “A” stands for “all seeing,” “all knowing,” “all of Spotify’s payouts,” and—as if to steal thunder from Elvis Costello (and, by extension, Swift’s own prodigal daughter, Olivia Rodrigo)—”Alison.” If that seems far fetched, that’s just your inner round-earther talking. You and “gravity” can share a nice chuckle as you drift into the “horizon.” Tell the Midgard Serpent I said “‘sup.” For those open to the truth (Taylor’s Version), a veritable traveling pants-load of revelation awaits. As any devotee will tell you, everything related to Swift is to be received as a s’more-like riddle, each layer gooier with meaning than the one that came before.

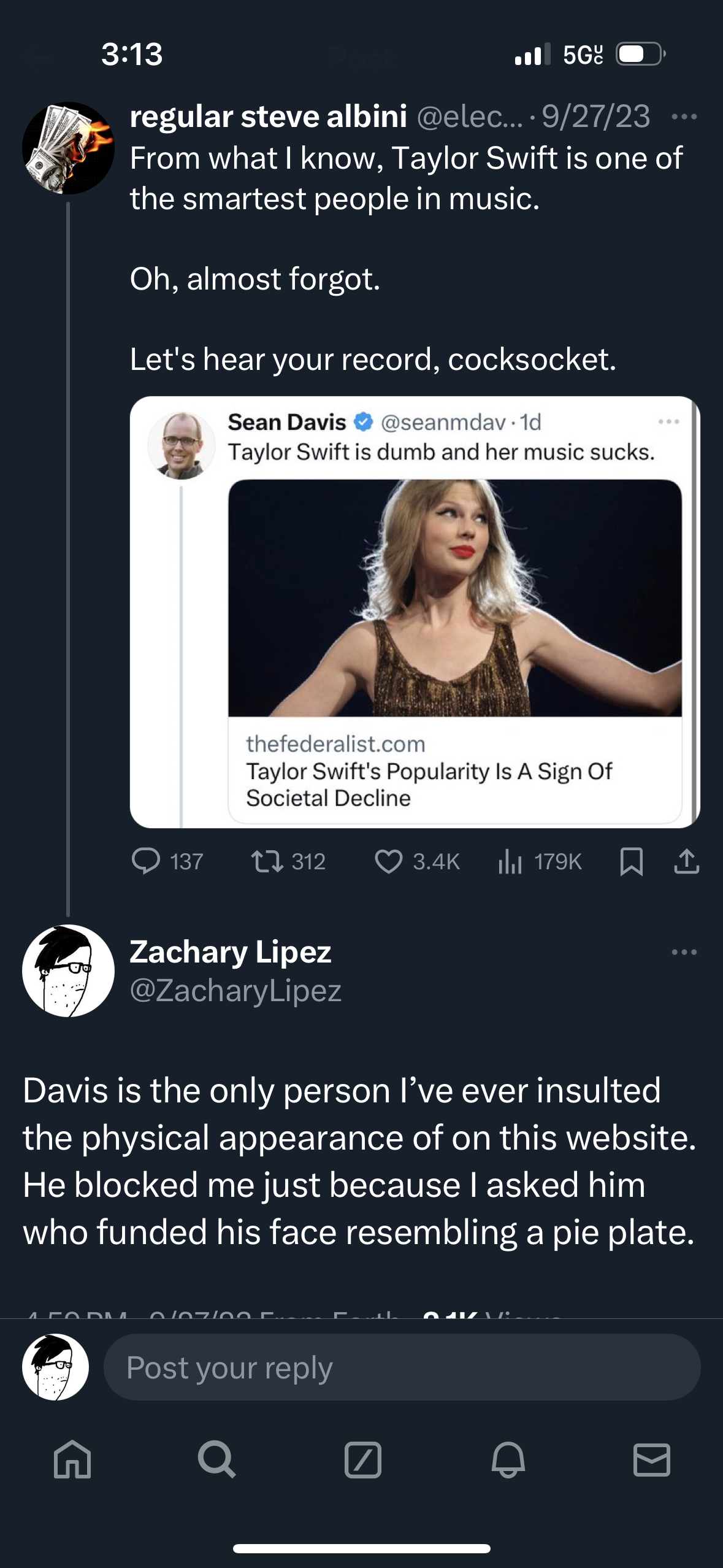

If there’s any doubt that every single neutrino of Taylor Swift’s cosmology carries meaning, then Swift’s new album intends to squash that heresy for good. The Tortured Poets Department is a Hubble telescope, aimed solely at Taylor Swift’s innerverse. Which, as an irrevocably expanding thing, is our external universe. The Tortured Poets Department is an album that’s presumption to universal relatability is backed by the NFL, Rolling Stone Magazine, RT, CNN, the CCP, and a shadowy alliance of Nashville’s Grand Ole Oprey and the Goo Goo Cluster Standard Candy Company of Tennessee. Not to mention the legions of flaxen-haired Torquemadas, Gaylor shipping magnates, and tender-straight witch hunters known collectively as “Swifties” (named for the celerity with which they will gleefully cut a motherfucker in a 1975 t-shirt).

Taylor Swift’s newest exercise in inter-dimensional hegemony is a 31 track album that’s two hour and two minute runtime outpaces that of Swift’s main competitors (Beyoncé and Einstürzende Neubauten) by forty-four and forty-eight minutes respectively. As The Tortured Poets Department bills itself as an “anthology,” it’s only fair to consider its length within that context. Therefore, to be fair, Swift’s album is forty-three minutes shorter than The Sire Years 1976-1981, an anthology of the first six Ramones albums. That Swift was able to produce, in the couple years since her last album (2022’s Midnight), an amount of art which the Ramones could only surpass (by forty-three minutes) over the course of five years is a testament to how far we’ve come as a poetry producing nation.

Amidst its magnitude,The Tortured Poets Department asks a similarly gargantuan (if coyly, phrased) question; who is afraid of little old Taylor Swift? One could just as easily ask who’s afraid of the wrathful Yaweh of the Little Old Testament? Who’s afraid of “Little Old Me”? Sane people, that’s who. Decent people, people with dreams of their own (no matter how comparatively meager those dreams may seem). People who value drawing breath and having a working social security number.

Music critics mainly. But in 2024, that’s just about everybody.

Scoff if you like. But consider that Kanye West, the last public figure to repeatedly deny Swift her flowers, was an internationally respected rapper and producer before he eventually—in a series of revenges served so cold that insinuations of a bright-eyed mastermind behind them might seem improbable—got slapped down so hard that he forgot both his last name and that the Holocaust happened. Consider the careers of Tina Fey or Katie Perry, the most notable female celebrities to publicly cross swords with Swift. Consider Mean Girls The Musical. If you can’t believe a cautionary tale you haven’t seen with your own eyes, there’s undoubtedly a touring production of Fey’s comeuppance playing a tertiary market near you. Fifty dollars will get you orchestra seats for the show’s extended run in Utica, NY. Who knows, maybe the voice of Regina George belting out “Meet The Plastics” will sound vaguely familiar, like a teenage daydream.

Consider Mean Girls The Musical The Movie. If you do, you will be one of about fifteen people on the planet to give any consideration whatsoever to the first feature film to be visibly ashamed of what it was; not even a watered down version of the original, but instead a squishy remake of a Broadway trifle based on source material that’s spark had long ago abandoned its makers. Mean Girls The Musical The Movie’s promotional material put so much effort into pretending that it wasn’t a musical that one could almost suspect that a little old birdie had sent word to Tina Fey that if there was a hell for women who didn’t support other women, there was an even hotter hell in store for eye-rolling bitches who didn’t know enough to stay in their own lane.

The above, of course, are just examples. And maybe examples based on varying degrees of supposition. No need to gild the lily further. Point is just that, unless you actually want to look (as Lot’s wife did) at what you (like the Pharaoh) made her do, some caution is warranted.

On the other hand, talking about Taylor Swift is fun. Certainly oodles more fun than talking about the fading faith known as “indie rock. A once vital religion, indie rock is now so diminished as to rebrand itself as a “community,” like one of those soft-boi-dippy sub sects of Christianity forced to accept cultural satanists and skateboarders just to fill the pews. In those pews the discourse is dominated by shoegaze taxonomy, weaponized autism, accusations of zionist-coded bass drops, and all the other Lord of the Flies style maneuvering required of any artist who hopes to graduate from basement shows to baby-font billing at the bottom of the Coachella lineup. If that’s the alternative, I’ll take a Big Top Jesus every time. It is inconvenient that so much of Swift’s art is tedious. And it ain’t great that Swift briefly mobilized her forces against the Ticketmaster/LiveNation monopoly but eventually said “fuck it,” threw a couple baby red pandas into the propellers of her private jet, cosigned CTI with a kiss, and threw thirty-one sure-fire hit singles up on Spotify (either to game the Billboard charts or just so Joni Mitchel and Neil Young knew that they could, in fact, go fuck themselves). But in a time where shared cultural moments are almost exclusively violent and terrible, I’m grateful to the lady for providing some Beatlemaniacal, moon walking, where’s-the-beef-ing, communal, nigh-inescapable sense of wonder; the kind of sun-blotting fluff that this country will possibly never see again. Beyoncé’s hegemonic moments will always bear the freight of certain cultural/historical realities (and will therefore have some larger meaning whether anyone likes it or not), Swift has created a perpetual spectacle machine which acts (with, of course, the benefit of white privilege) as something only about Taylor Swift, burdened by only the stakes she allows in. There was a brief moment a few years ago when American jankiness threatened to drag her in but now—especially now, with Kanye conveniently exiled to his pussy sarcophagus—Taylor Swift has excluded herself from that narrative. That’s why her lyric about wanting to live in the 1830s, minus the racism, makes sense to her and her fans. In Taylor Swift’s American timeline, stress is internal, like a m’lady catching the vapors, and all historical strife is backdrop. Thusly, Swift is an American dream where Daddy Warbucks made his dough building pickup trucks and her zeitgeist are the kind of emotionally zoomed-in, but still huge, moments where we skip past the dreariness of WW2 and focus on the important stuff; that sailor laying a juicy one on that nurse. Every album release is the Trial of OJ but with the only crime of passion being the passion Taylor Swift has for entertaining her fans.

*************

It should be noted that, regardless of any hyperbole used for rhetorical effect, the reality described above is just one reality. One doesn’t need more than passing familiarity with science fiction literature regarding parallel worlds (though, for those interested in a brush up, Crisis on Infinite Earths is currently streaming on MAX) to know that there are endless timelines, diverging at different points and happening simultaneously. Even within our Taylorverse, there are realities where Swift is not the north star of all existence. Realities with names like “Not America,” “Diaspora/immigrant communities within America,” “Black Twitter,” and “hardcore,” where vast swathes of people have their own Taylors (such as the “Courtney Taylor-Taylor” demiurge worshiped in some primitivist societies scattered throughout the hollows of the Pacific Northwest), or even—hard as it might be to imagine for those of us of certain socioeconomic or ethnic backgrounds—no Taylor at all.

To illustrate how these fascinating parallel worlds can overlap with ours, I can mention one time that myself and my wife were walking around our neighborhood. We live in Tribeca, an extremely expensive neighborhood which we’re able to live in through the miracle of rent stabilization and the fact that, after leaving Afghanistan, members of my wife’s family settled in the neighborhood in the 1970s, when there was hardly anybody regularly this far downtown besides a few enterprising cannibalistic humanoid underground dwellers, the Mudd Club staff, and a single Mister Softee truck driven by Catherine O’Hara. Now, of course, all the cannibalism is related to real estate and the Mister Softee is a Van Leeuwen. And, as we would discover, Taylor Swift lives here.

We found this out when, on the day in question, we encountered a long line of young people, dressed to work the floor of Forever 21, lining up to seemingly get into an empty slot of sidewalk.

My wife, a curious type, asked one of the young people “What are you guys doing?”

One of them, with a face as open and friendly as a cheese curd dispensary, replied “we’re waiting for Taylor!”

My wife, not one to usually clutch her pearls, was aghast. She blurted out “You’re standing around, waiting for a famous person?”

The young people looked at my wife as though her foreignness had only just been made clear. They nodded.

My wife said, “But… you’re fucking grown ups!” before she could catch herself. We got off that block as fast as our feet could take us. I, living in the Taylorverse, took it all in stride. My wife, raised as she was by refugees and Nirvana, therefore existing in the universe that exists in this one but on a different vibrational plane, was shaken for the remainder of the afternoon.

In the first chapter of David Byrne’s How Music Works, the Talking Head uses his Writing Hand to expound on his belief that music—before amplification, or even electricity—was exclusively live performance. Therefore music’s sonic characteristics were determined by the context—from open fields to opera houses—within which the music was performed. Even as technology progressed beyond drums circles and plus-size valkyries, its composition continued to be determined by factors such as how slapilly a bass would bounce off a wall and how many angel wings needed to be stuffed into an organ pipe so their lil’ angel shrieks would hit the cathedral’s high ceilings just right. Byrne goes on to write that the invention of stadium rock addressed a need for a uniformity of sound, one which could compete with concrete walls built for football, fascism, and the occasional “Disco Sux” rally. The result was “steady-state music (music with a consistent volume, more or less unchanging textures, and fairly simple pulsing rhythms).”

A few pages later, Byrne says “If there has been a compositional response to MP3s and the era of private listening, I have yet to hear it.”

How Music Works was published in 2012. David Byrne wouldn’t have to wait long to find out what music composed to be played within a collapsed star might sound like. While countless Swedes answered the call to make popular music for bluetooth and streaming services, only one man has, since his first collaboration with Swift (on 2014’s 1989), developed a singular sound which combines the best of both black holes and cottage-core.

Jack Antonoff was once best known as Lena Dunham’s ex and as the mastermind behind Bleachers, a band that, in the ‘80s, would be featured on every teen sex comedy soundtrack (whenever Oingo Boingo was unavailable). Having anticipated—in a way that David Byrne could never have dreamt, despite the seeming inevitability of “This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody)” becoming the de rigeur song of choice for countless “free spirit seeks financial stability” profiles on Raya—the market for a pristinely evocative vibe, Jack Antonoff nowadays serves a far more impressive function within the pop landscape; as the aural equivalent of Vishwarupa, Destroyer of Worlds.

Given how deeply Antonoff has come to be despised—with his production/songwriting style having become a sort of shorthand for the onset hyper-normality which has infected every nook and cranny of contemporary culture, from Joe Biden’s rictus grampapacy to the cloud blue denim which even our urban hipsters have adopted—it’s tempting to defend him. But I’m afraid that, even for the serial contrarian, some things are beyond reconstruction. Combining the worst of the two scenarios (stadiums and MP3 players) described in Byrne’s essay, Antonoff has emerged as a visionary in the field of anonymising insularity. His incongruous mix of brutalist songcraft (imagine The Vessel at Hudson Yards if it was a single story high) and anodyne signifiers of intimacy (largely, these days, conveyed via synth sounds so warm and pre-churned they may as well be saliva) makes empty stadiums of the listener’s skull.

(The second half of the album is produced by Aaron Dessner. Dessner is best known as the frontman for The National, a better-than-solid guitar act which would be even more successful if the traditional first dance at weddings had a corresponding ritual when couples divorced. The second half of The Tortured Poets Department is probably fine.)

Consistent with Antonoff’s catalog, no contrarianism is up to the task of defending Tortured Poets. As someone committed to disagreeing with his peers, I tried. Seeing The Tortured Poets Department get Swift’s worst notices since Reputation (2017’s exploration of electro-trash ‘n’ vaudevillainy which had a peppy spite which made the singer the most relatable she’s ever been) made me want to stick up for it. I even toyed with comparing it to Tusk, Fleetwood Mac’s double album which was seen as a bloated mess at the time of its release and is now correctly seen as a bloated mess of psychosexually antic, coke-fueled genius). It was worth a try. After all, when the Swift/Antonoff system works, as it occasionally does on songs like “The Archer'' (off of 2019’s Lover), you get music moving enough that I almost almost-cry every time I hear it drifting through the aisles of a Walgreens pharmacy.

In this case, defending is off the table. Even while finding the album’s often admirably silly lyrics (Charlie Puth as an underappreciated artist? Sure, fuck it! Why not?) a vast improvement over the deathless beauty Swift reveled in on her previous indie folk albums, and even while acknowledging that Swift’s lyrics are far better than those of other serial solipsists working similar ground (like, for instance, dudes from Weezer or Jawbreaker) overwhelming feeling that the singer is less plumbing her own depths than doing a response video to YouTube comments proves to be an insurmountable obstacle. Swift’s poetry being “bad” isn’t the issue. It isn’t, and anyway the poetry police can eat a dick the size of Rough and Rowdy Ways’ press kit. But if you’re going to use “tortured” as a selling point, you can’t outsource the sounding like you give a shit to Florence + the Machine. With even the egregious use of “fuck” coming off as distantly affected as a sassy stenographer reading Body Count lyrics onto the congressional record, there’s nothing here which couldn’t be expressed with considerably more force by vigorously scrolling through (instagram gossip site) DeuxMoi’s stories while punching in a Tears For Fears preset.

The hedging is baked in. On the album’s title track, Swift makes a pointed reference to Chelsea Hotel, but only to frame the comparison as something to deny. If Patti Smith is going to be posited as a point of comparison which would come to a single mind on earth; if it’s going to be suggested that any person might imagine either Swift or 1975’s problematic bohunk, Matt Healy (or the other possible subject of the song, Joe Alwyn) hanging out in a messy hotel room, telling the other that they “preferred handsome men/but for me, you’d make an exception” or whatever, then MAKE THAT ARGUMENT. With your entire chest. Telling us that you’re only half damaged is just a waste of everyone’s time. There aren’t any unmade beds in The Tortured Poets Department. There are no piss factories because I’m not sure any of the parties involved have ever peed in their lives. At least not without running the faucet as loudly as possible. In this arid landscape, De Blue Nile is just a band in Glasgow. In contrast to all the bumps involved in the making of Tusk, Tortured Poets Department is devoid of any topography whatsoever. Absent peaks or valleys, it’s not Leonard Cohen or L.A. soft rock, it’s Kansas.

Look, I got better things to do with my time than trying to convince 26-32-year-old sociopaths that their fandom is an affront to the gift of life which, against nearly unimaginable odds, they’ve been granted. If you’re inclined to stan some artist you don’t know, who wouldn’t pick their own teeth with your bones, then go for it. Perhaps, if your brain truly is nothing but Disney-fied slurry, it’s time to consider walking into the ocean and letting the void in your psyche become some other little mermaid’s problem. But I don’t believe anyone is beyond redemption and, anyway, who am I to judge? I myself loved cocaine a lot, for a long, long time. And loving that shit is not much better than being emotionally invested in sending death threats to people who disagree on the metric tonnage of cunt being served by one’s pop star of choice. Anyway, the walking-into-the-sea option (or a nice pivot towards religious extremism—anything to focus one’s antic bonker-ism into some less pathetic stakes) is applying individual (possibly monkey-pawed) solutions to a systemic problem.

Because where would all these people actually go without Taylor Swift to sustain both their interior lives (as it were) and their ferocious externality? It would be ‘80s deinstitutionalization of mental health all over again. Instead of resultant mass homelessness, we’d have an epidemic of feral Social Media Coordinators kicking over brunch buffets for reasons unknowable even to themselves. We’d have buffed out militias of lordless gym-ronins, gayer than the navy but with a placeless, insatiable rage. The dude from The National would wander the streets of Hudson, driven mad with the unshakable belief that he was destined to be more than merely very successful. Without Antonoff and Swift around to do what they do best—contain, catalog, and smother unruliness—chaos would reign.

With that in mind, I’m putting The Tortured Poets Department on Spotify again. I’ll listen to other music next year, when the album runs its course. Sacrifices are necessary for the greater good. I voted for Biden once and, since I shan't be doing that again, I can at least do this. Anything to keep the wolves at bay. Even when said wolves already gather a few blocks from my house, with their hope to catch a glimpse of their lupine goddess as ultra high as the waists of their jeans. Let the thirty one songs of The Tortured Poets Department run their interminable course. Let the lights burn fluorescent. Let the air be centrally conditioned. Let the ambient sounds of the city die at the windows of my apartment. My heart carries the torch for a world where Charlie Puth is the weird one. My hands clap in whatever the opposite of polyrhythm is. My mind is dancing in the rain in a sundress, next to a pickup truck in one of the Carolinas. My soul is sticking its tongue out, flashing dual peace signs in front of a Central Perk pop-up. As The Tortured Poets Department cycles through its 122 minutes of Swiftian lore, my entire being belongs to the downtown lights. And those lights are coming from the Fulton Street CVS..

Thanks for reading. Please share and subscribe. Please subscribe to CREEM (next issue is the movie issue and I interviewed Penelope Spheeris and Kid Congo!). Also, if you feel like critiquing me, Zohra and I did a couple cover songs (and all proceeds go to Social Tees). Ok that’s all. I’ll write about Steve Albini soon.

Ceasefire now. Free Palestine (in whatever way is possible… one state, two state… I don’t care. Just end the ethnic cleansing).

See you next time,

Z